Marissa’s Books & Gifts

“The man who helped me some fifty years ago got me my first book. I am now passing it forward.” Cindy Dumas, owner of the magnificent Marissa’s Books & Gifts, named for her first granddaughter, was born in San Francisco and moved to Utah prior to beginning junior high. By the time she arrived, school already felt hard. She remembers herself as a struggling student, trying to figure out what she had missed and why she could not catch up. Then, at age eleven, a teacher took an interest in her, and everything shifted.

Cindy can still trace the arc of her life back to that moment in the 1970s, the day her teacher put a Nancy Drew book into her hands. As a grown woman, she is still moved by the way one person’s attention changed her relationship with learning. She began reading constantly. Her confidence rose. Even her math scores improved, as if the simple act of understanding words on a page opened every other door.

Then, one day, the class went out for recess. “When we came back, he had died in the classroom.” The children were stopped from going inside. Cindy remembers the ambulance, the confusion, the way adults tried to explain without really explaining. There were substitute teachers, then more substitutes, and the classroom carried on, but the teacher who had made her feel seen was gone.

It was traumatic, and it was also clarifying. Cindy never forgot what it meant to be helped at exactly the right time, and she never forgot what it meant to suddenly lose the person who believed in you. From that moment on, she carried with her a clear understanding that “If children are struggling in school, if they are not reading well, then they will struggle in all of their courses, and in life if they are not recognized.” Marissa’s exists because of that realization. It exists as a place where children are seen, where books are placed into waiting hands, and where a single moment of encouragement can quietly change the direction of a life.

For Cindy, growing up, money was tight and stability was not guaranteed. She describes her family as dysfunctional long before people used that language freely. It was essential for her to work a string of jobs through high school because her family needed the money. Her father drank heavily, and the strain of that shaped the household in ways that did not always show from the outside. Books became both comfort and escape, and when buying them was not possible, the library was. “We did not have a lot of money, so a lot of our needs were not met.”

Cindy did not graduate with her class. She had finished the work, but she was short on credits after time away to earn money, and she carried that unfinished piece of her education into adulthood. At twenty-eight, she went back - and she did not go alone. She and her husband had married young, and he was short on credits as well. They returned together, and they graduated together, with their two young children in the audience. That moment stayed in their family story. Her youngest son, Jeff, who hated school with a force that still makes Cindy laugh, joked later when she pushed him to do his work. “Why, I have until I'm twenty-eight.”

Jeff did not actually wait that long. When he finished high school, he wrapped his diploma and presented it to his mother, a quiet thank you for the example she set. Today, that same son owns a successful construction company in the Salt Lake Valley, building homes and building a life that looks very different from Cindy’s childhood. Cindy elaborated proudly that her older son, James, is an accomplished composer and musician, and that each son is aware that as a child, she did not experience the kind of relationship with her own father that these sons have achieved with their own families.

The calling to become a bookstore owner did not arrive immediately after Cindy received her high school diploma, nor as a dream she had carried since childhood. Cindy is direct about that. “I never had an idea to own a bookstore. It came through a recession in 2008, through estate sales and auctions, through the practical work of finding discounted equipment her son could use when business tightened after the crash. One day, she met a young man in Ogden with an enormous warehouse of odds and ends, and she made an offer to clear it out. He accepted, then added one more detail. “In the back of the warehouse, there are 40,000 books. You have to take that, too.”

Cindy did not fully grasp what forty thousand books looked like until she was hauling them south, calling friends with trucks, borrowing warehouse space, and setting the whole thing up like a temporary bookstore because she could not stand the thought of books being thrown away. She told herself it would be seasonal, a short-lived effort to get books into people’s hands.

Customers appeared. Ken Sanders and Brett Eborn were among the first to arrive, and others recognized this grand opportunity. They were buyers with sharp eyes and quick instincts. Books moved fast. Then something surprising happened - after Cindy had sold tens of thousands, more books arrived. People started bringing truckloads, grateful to have a place to take them, certain Cindy’s little warehouse shop was permanent. "We are so happy to have a bookstore,” they exclaimed.

Cindy found herself with more inventory than when she began. What to do? A commercial real estate agent named Doug Stone kept showing up, and he kept insisting she stop thinking of the operation as temporary. “Okay, Cindy, here is what we are going to do. We are going to find you a space, and you are going to open a real bookstore.”

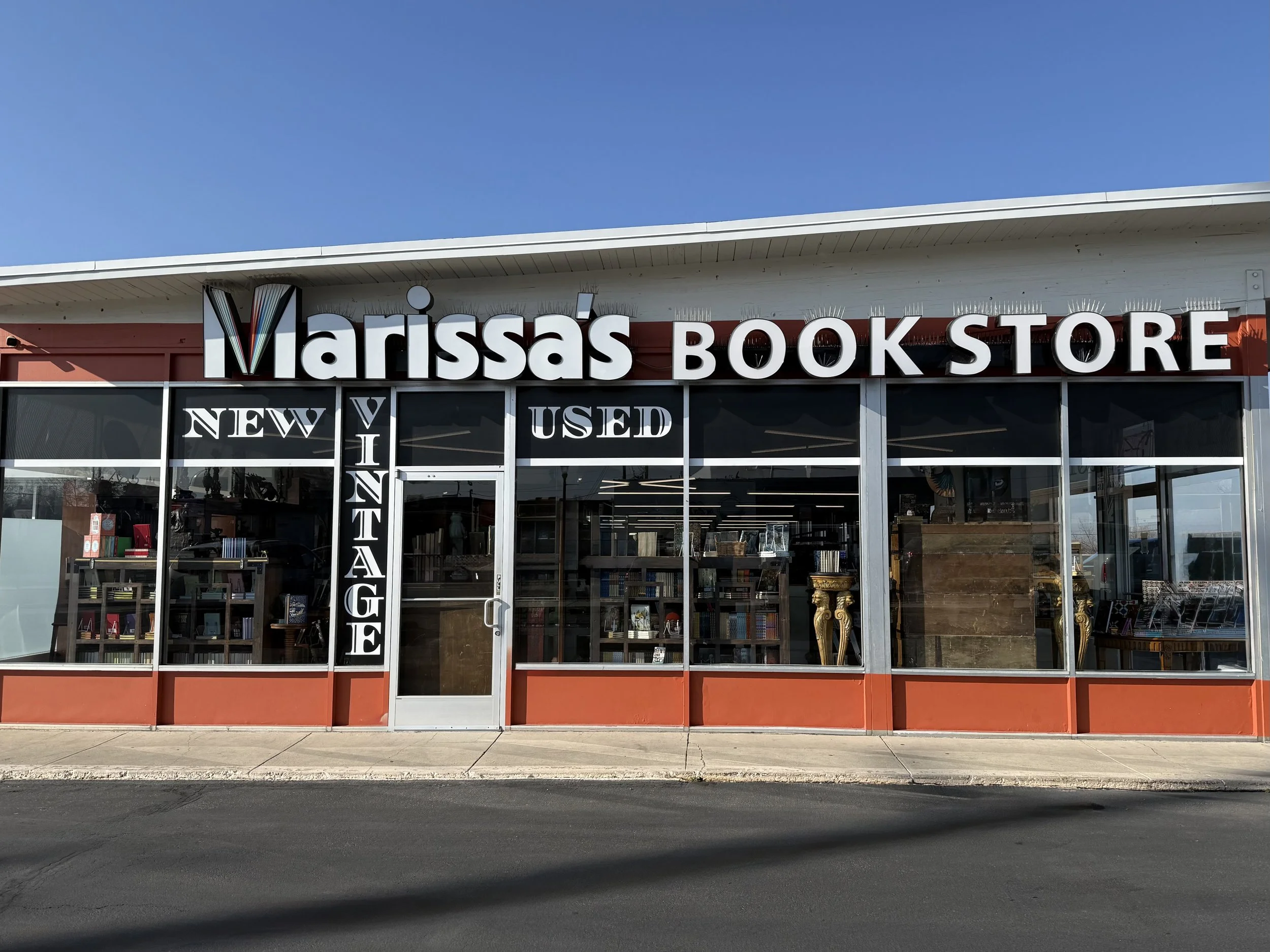

In 2013, Marissa’s opened its first true storefront in Murray. Over the years, the shop grew enough that Cindy moved once within the same complex, expanding the footprint and deepening the collection. Then, in 2019, with her lease nearing its end, the direction of the business changed abruptly. “They told us they were giving the space to AT&T, and they wanted to cut it in half.”

There was no gradual transition, and no grace period through the holidays. Cindy was told the store needed to close, immediately. What felt at the time like the worst possible blow became the pivot that carried Marissa’s to Millcreek. The space she found had been a tire shop - dirty, grimy, and unchanged from its former life - but Cindy could see past the grease-stained floors and concrete walls. “It ended up being the best thing that ever happened to us.”

With the help of landlords who worked alongside her, walls came down instead of going up. The floors were polished rather than replaced. The bones of the building were left exposed, and the store reopened in early 2020, just as the world shifted into uncertainty. What emerged was not only larger than anything Cindy had built before, but truer to what she had been imagining all along.

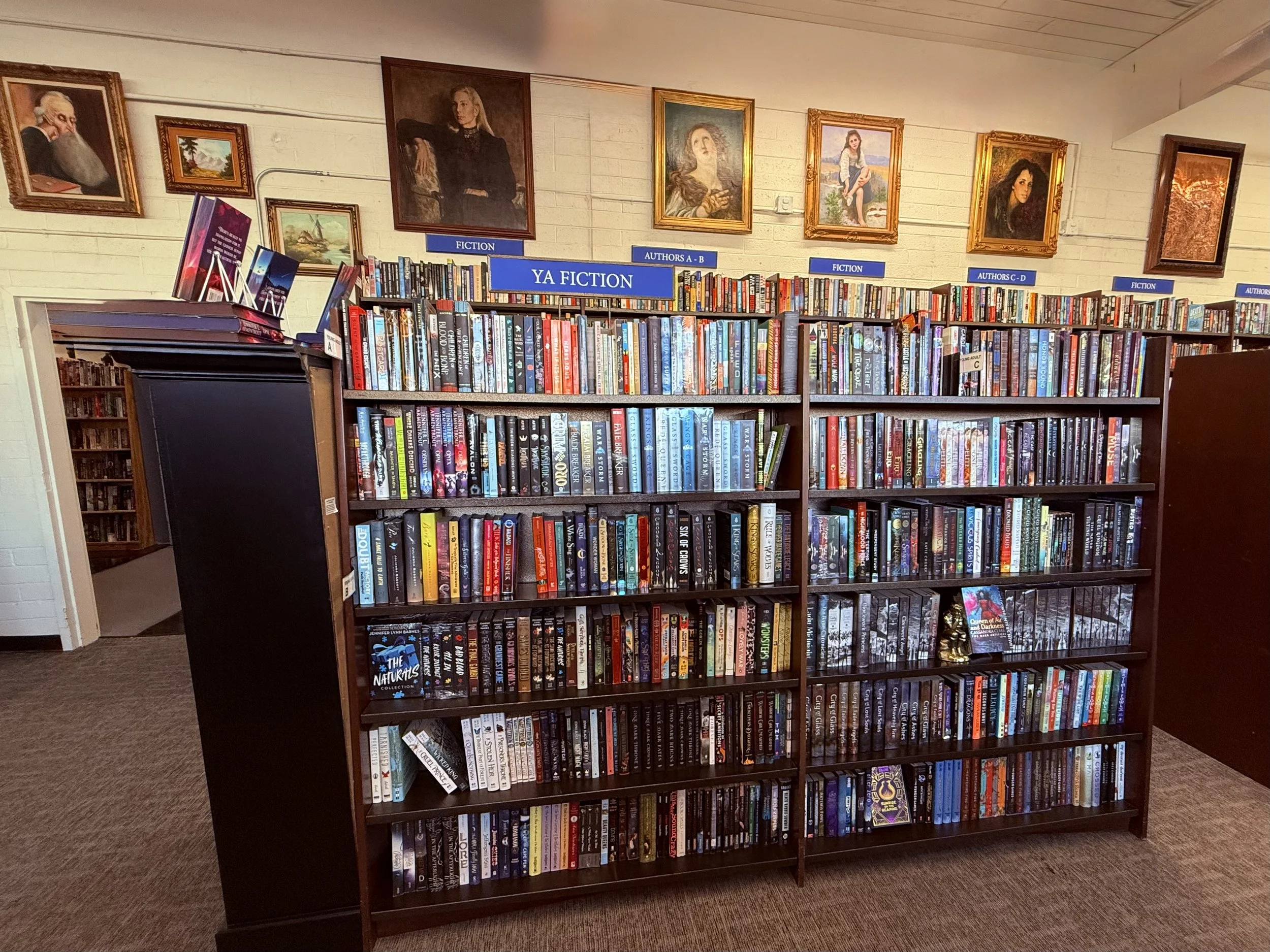

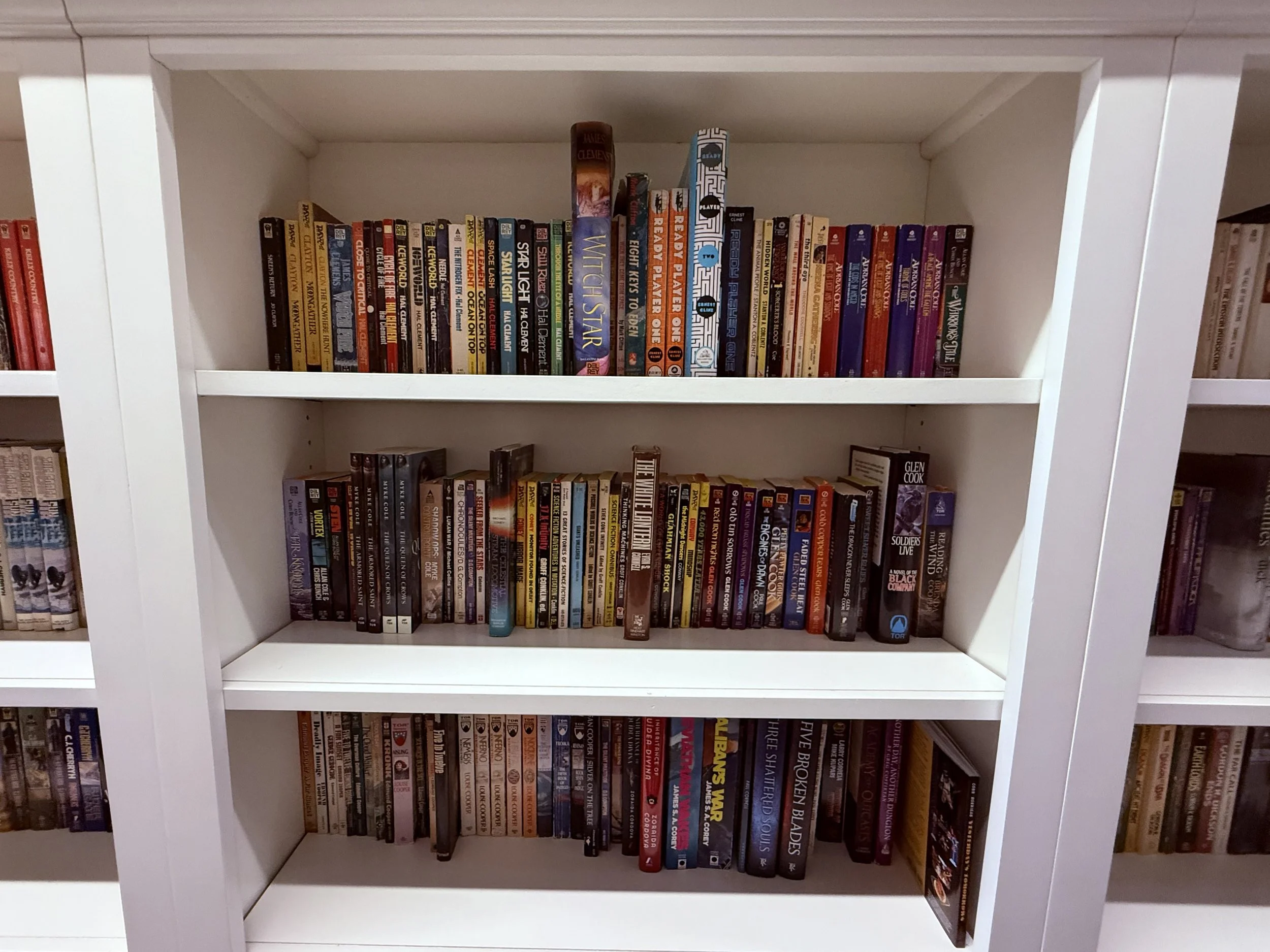

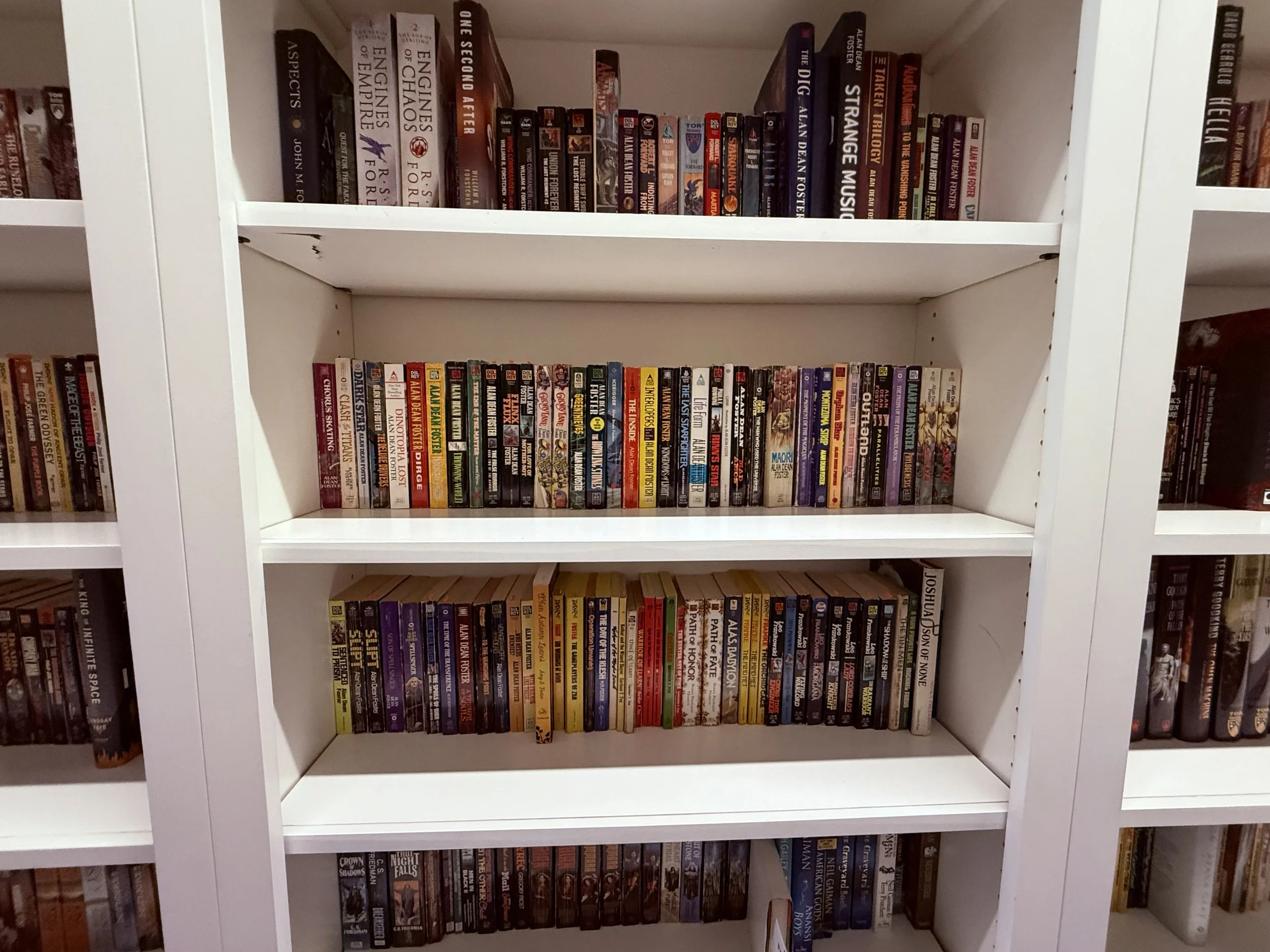

Marissa’s, as it exists in 2026, is not just a storefront. It is a major company, and it is larger than most people realize. Cindy bought a 6,000 square foot warehouse down the street and built a model that allows the store to supply itself, bringing inventory to the shop multiple times a week. She buys large, and she buys strategically, and she uses that scale not only for business, but for giving.

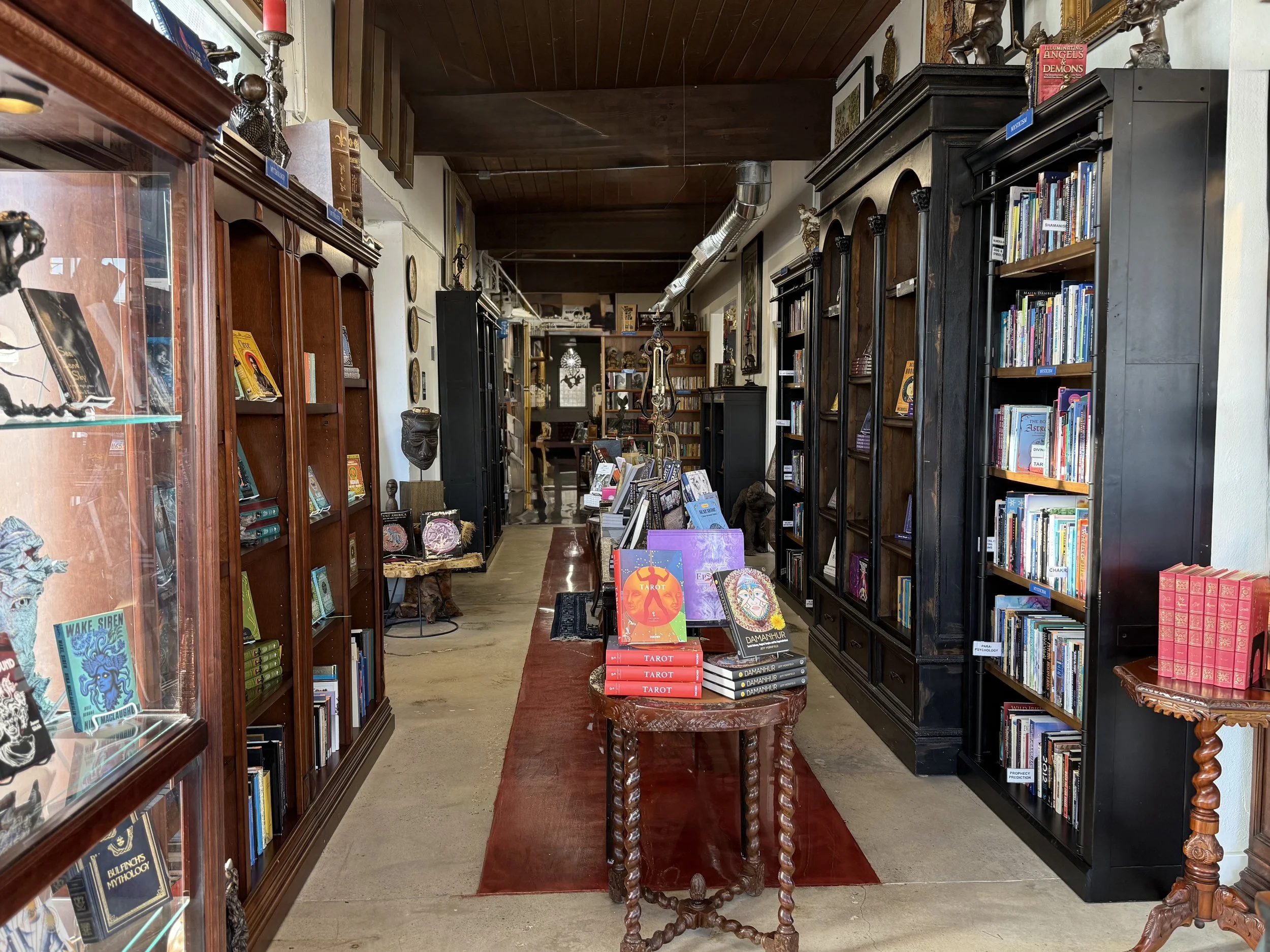

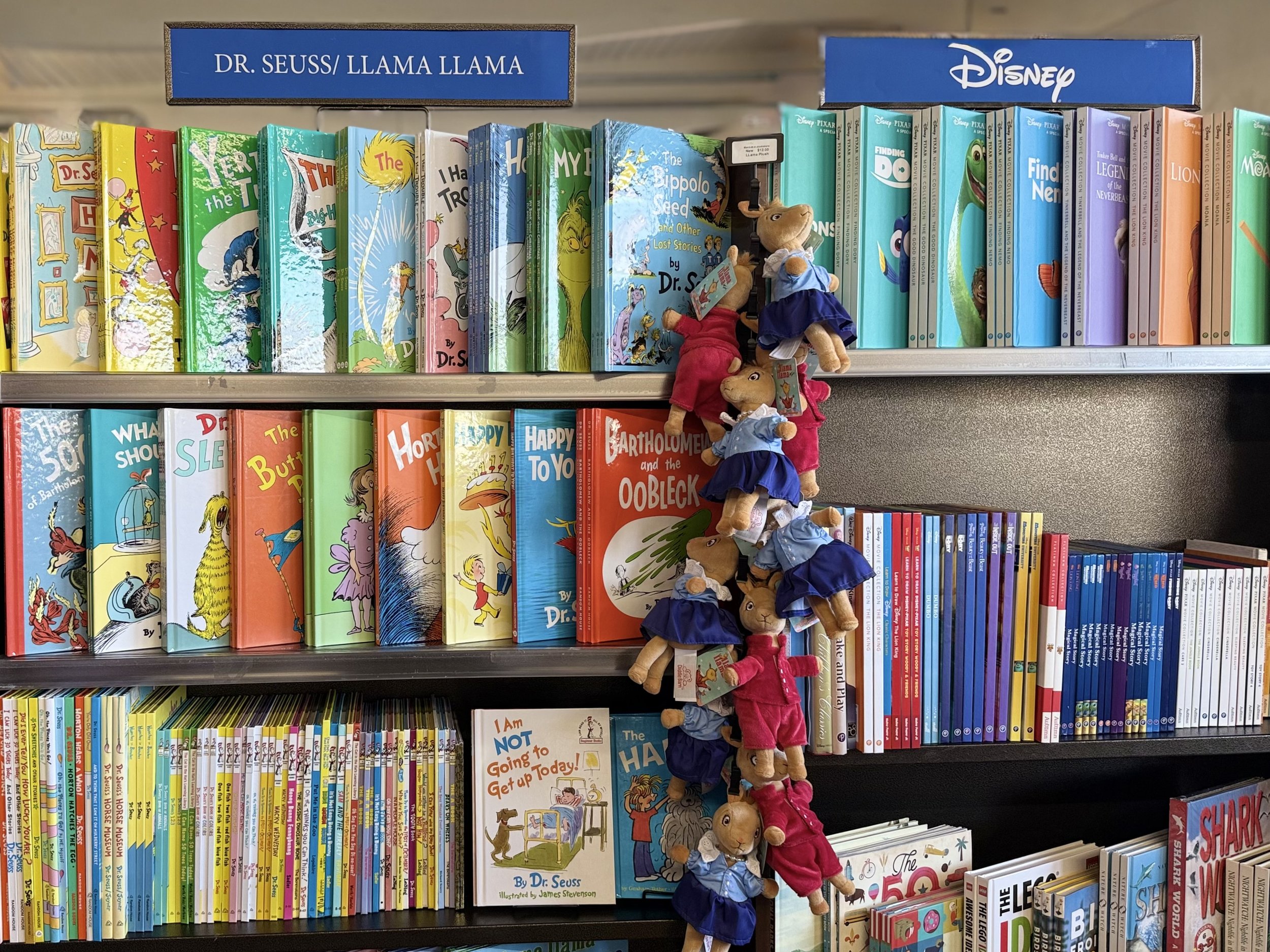

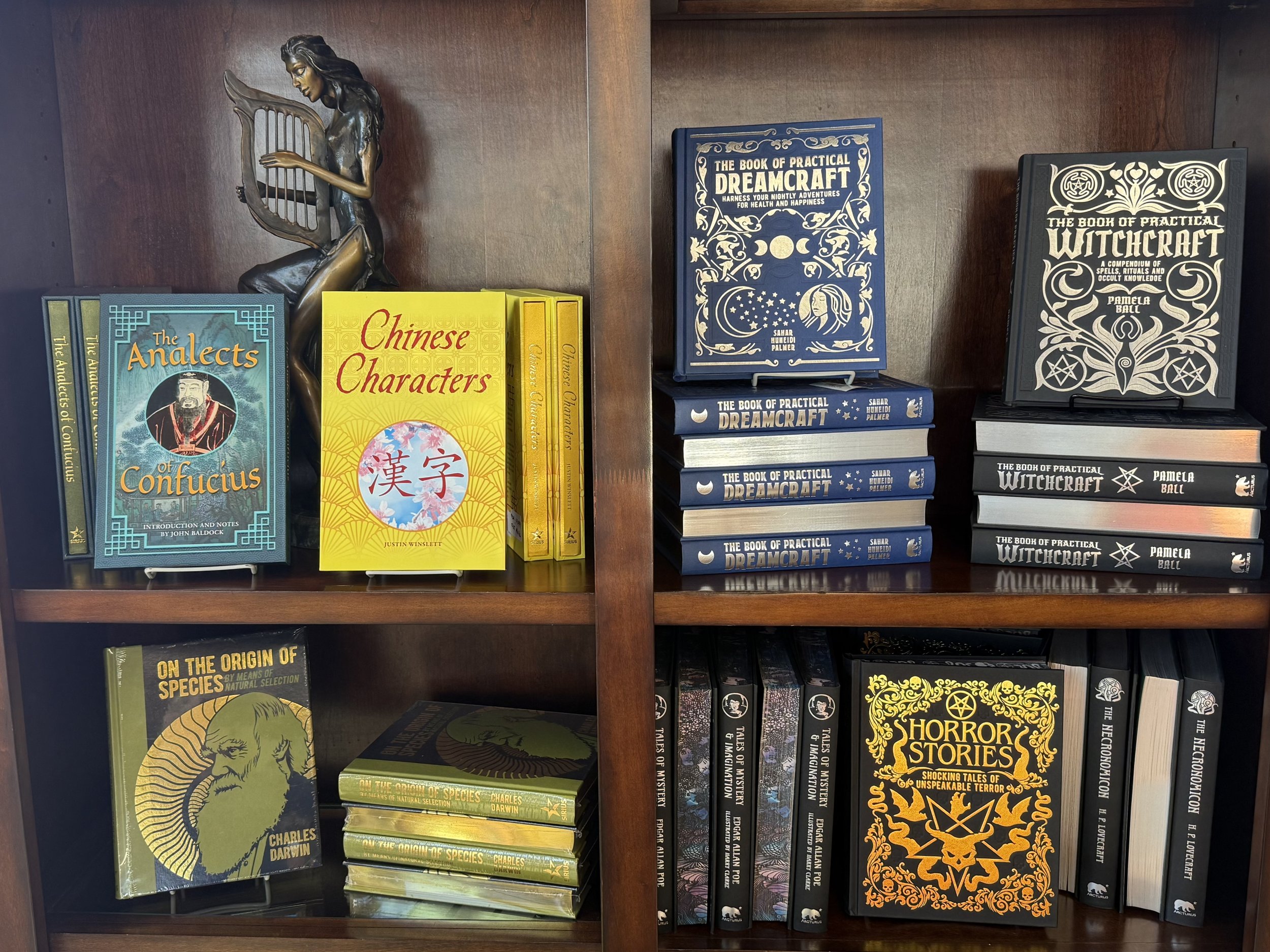

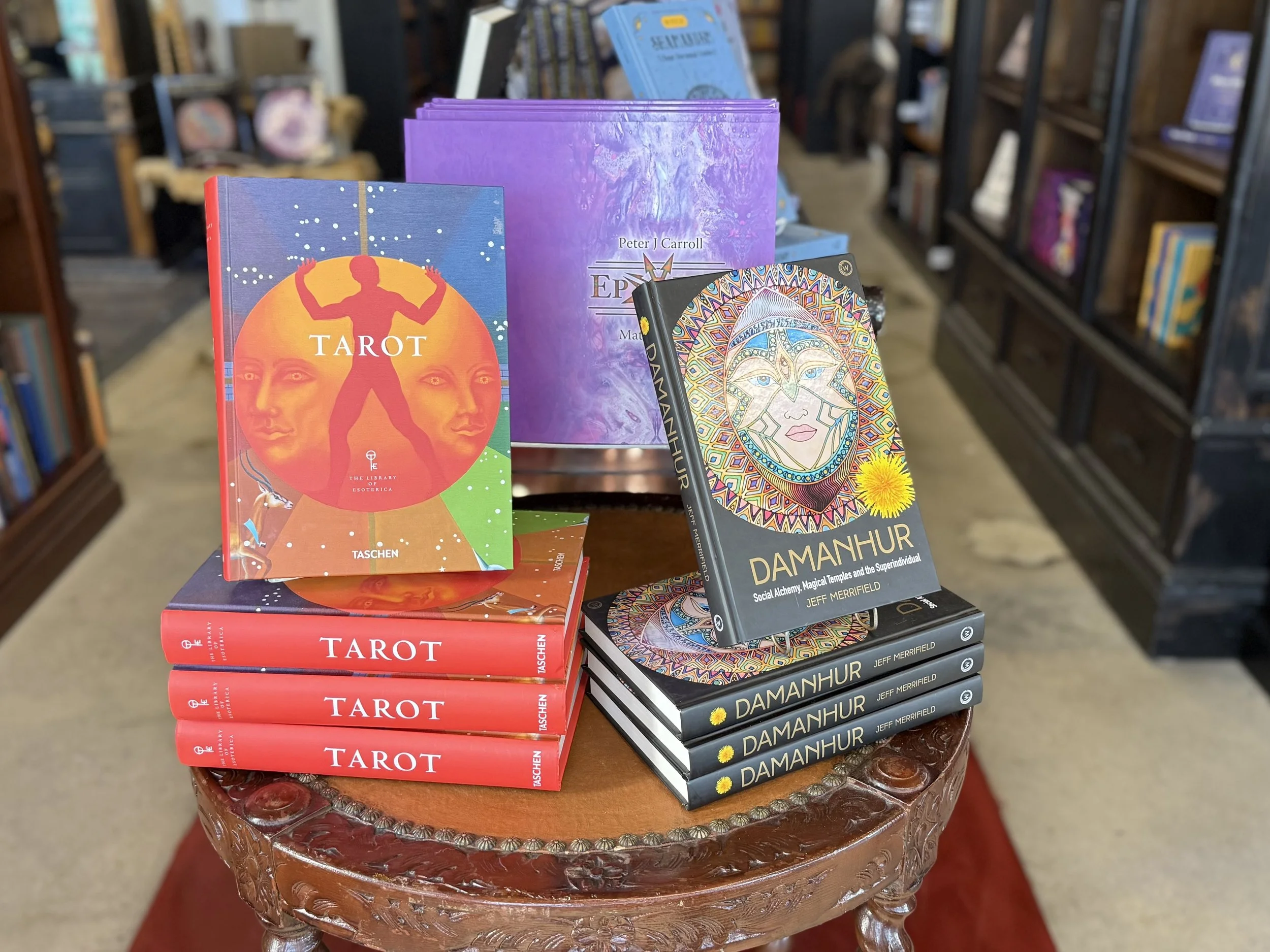

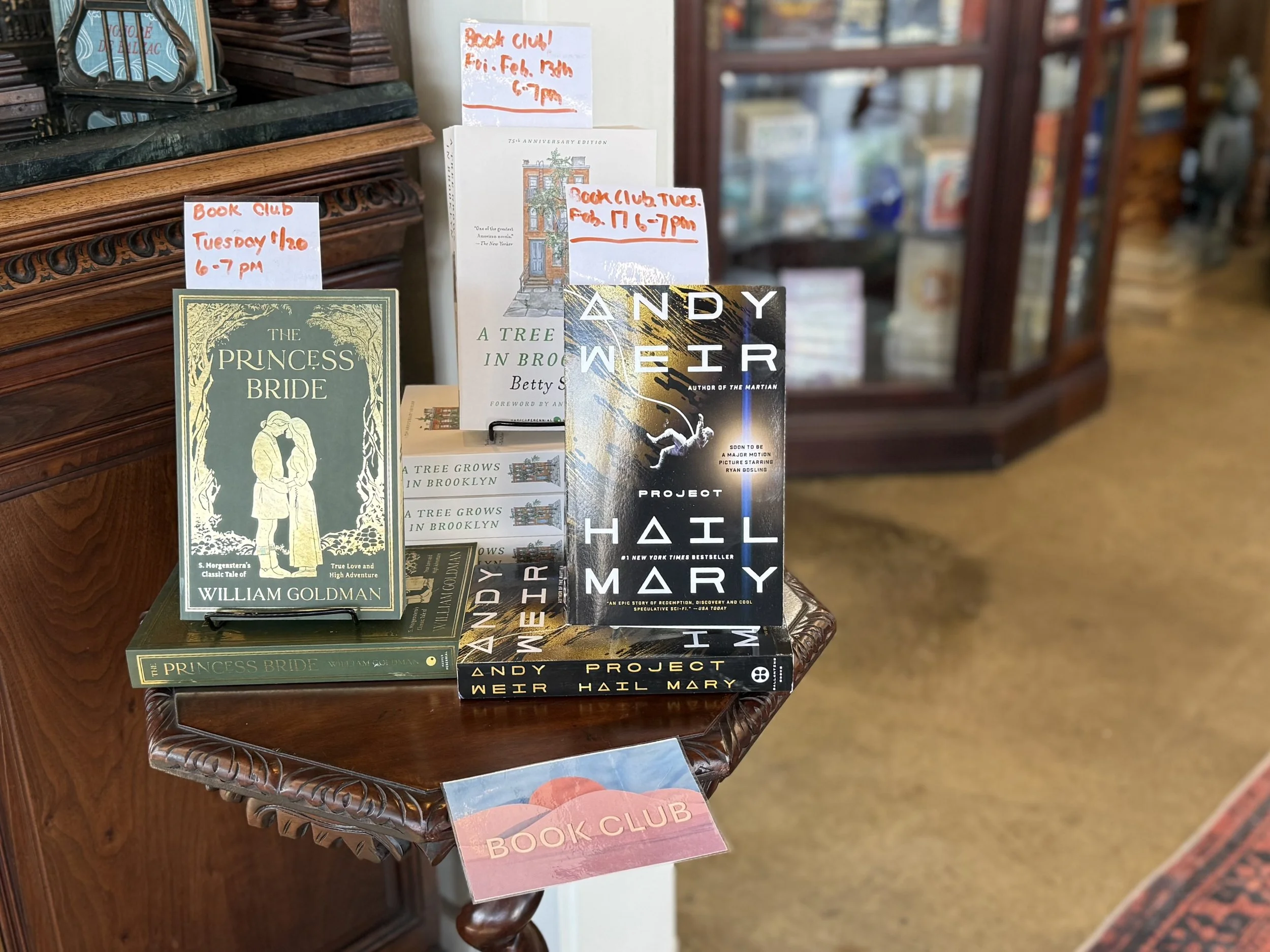

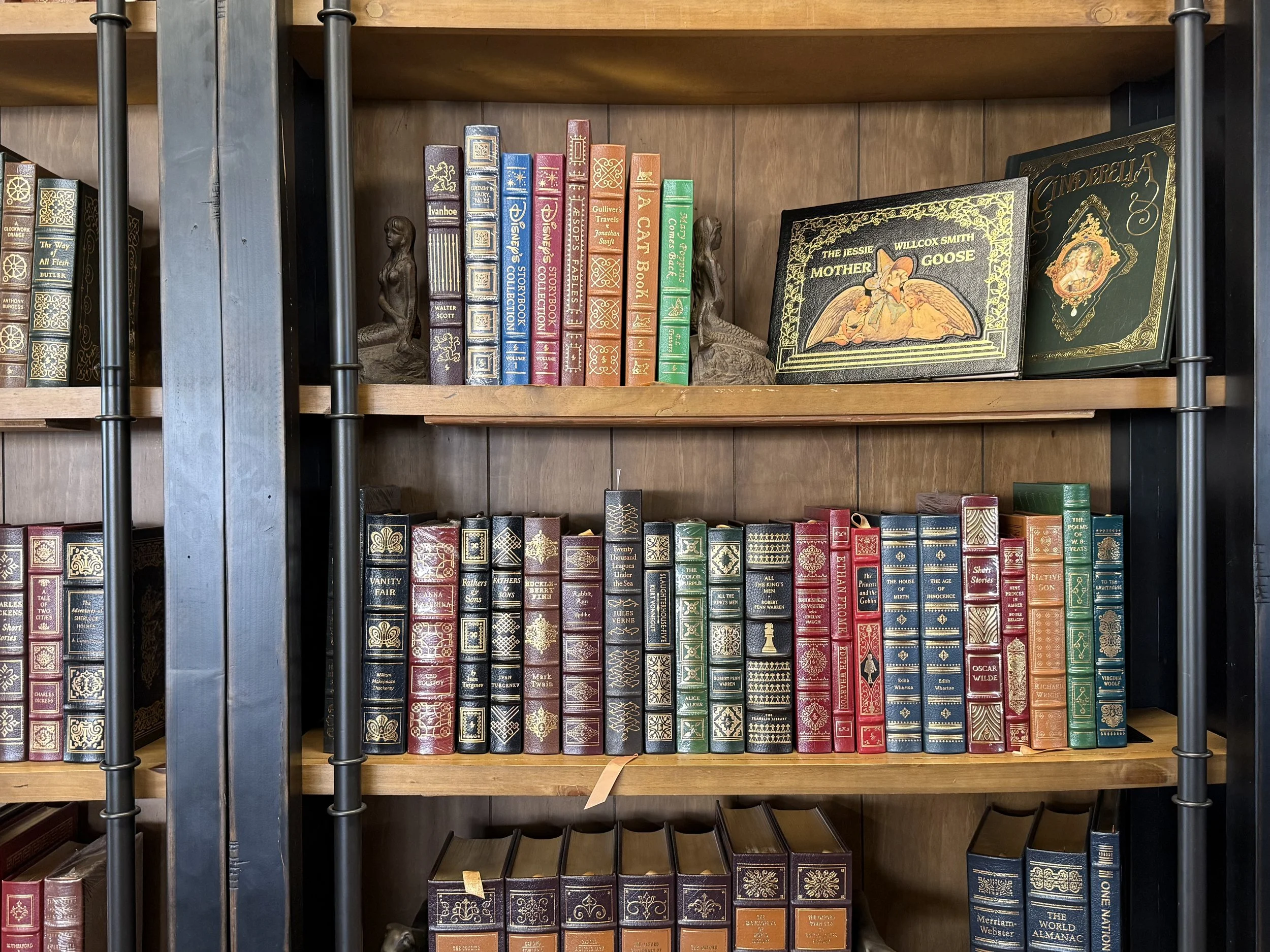

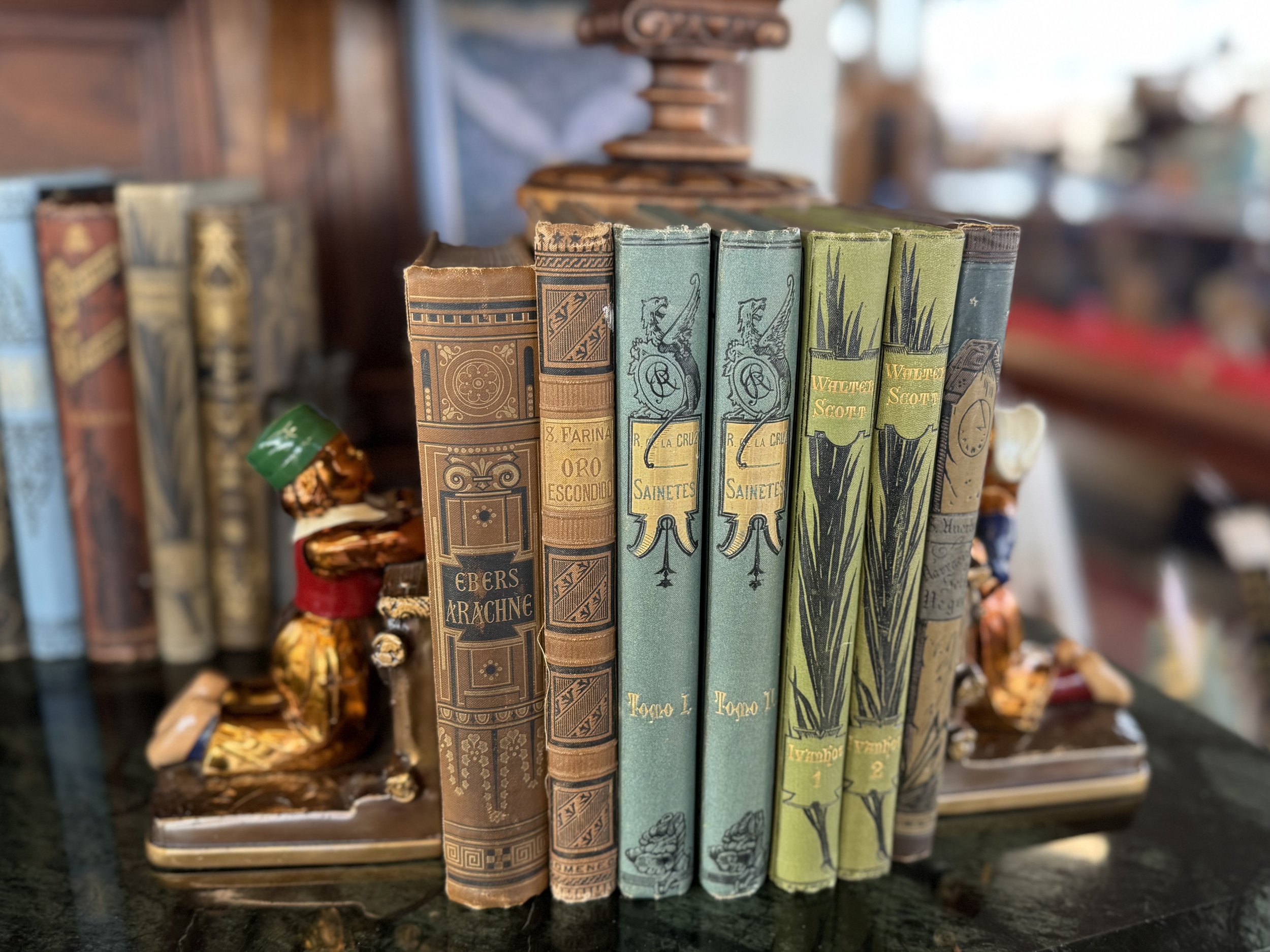

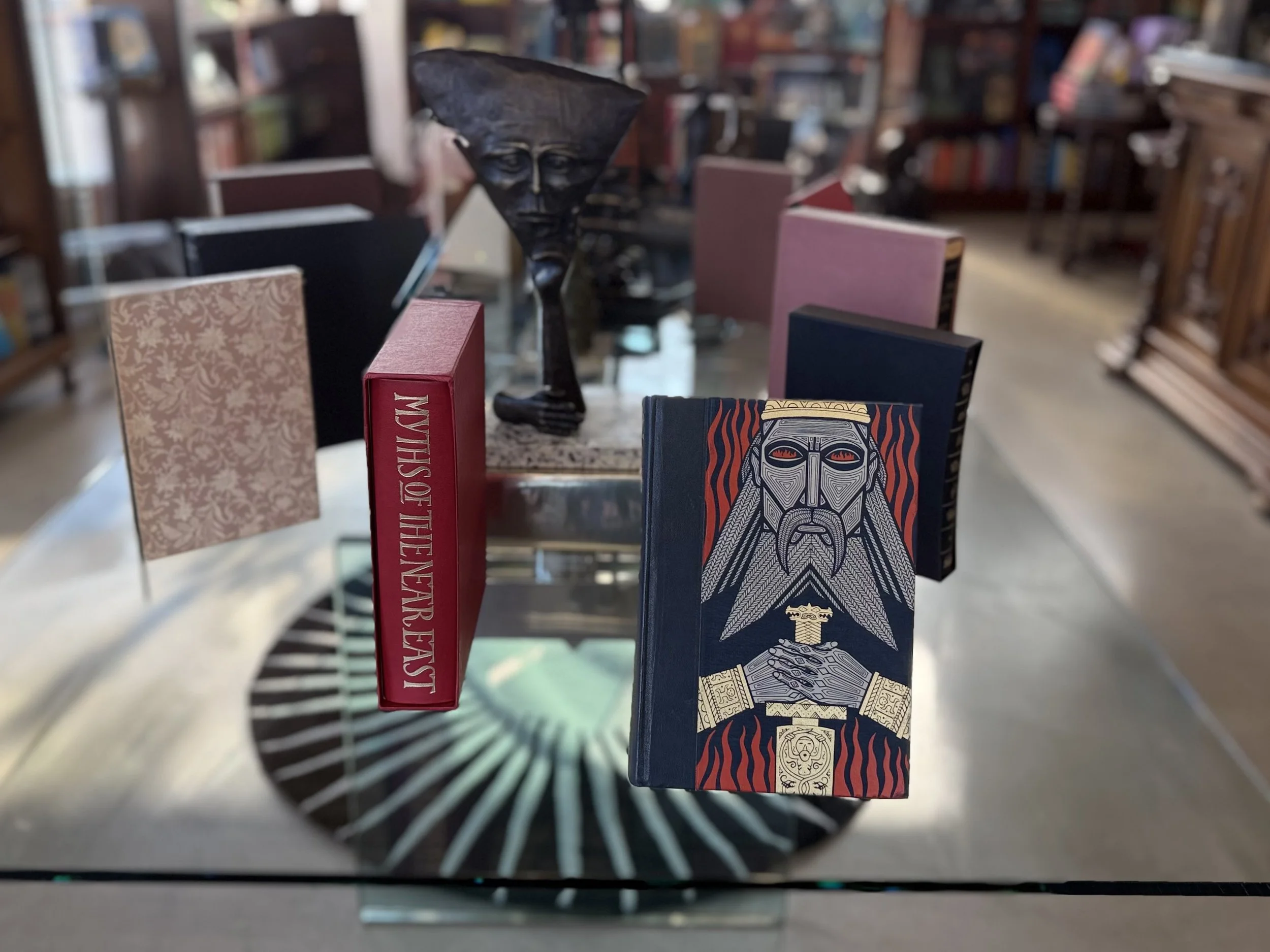

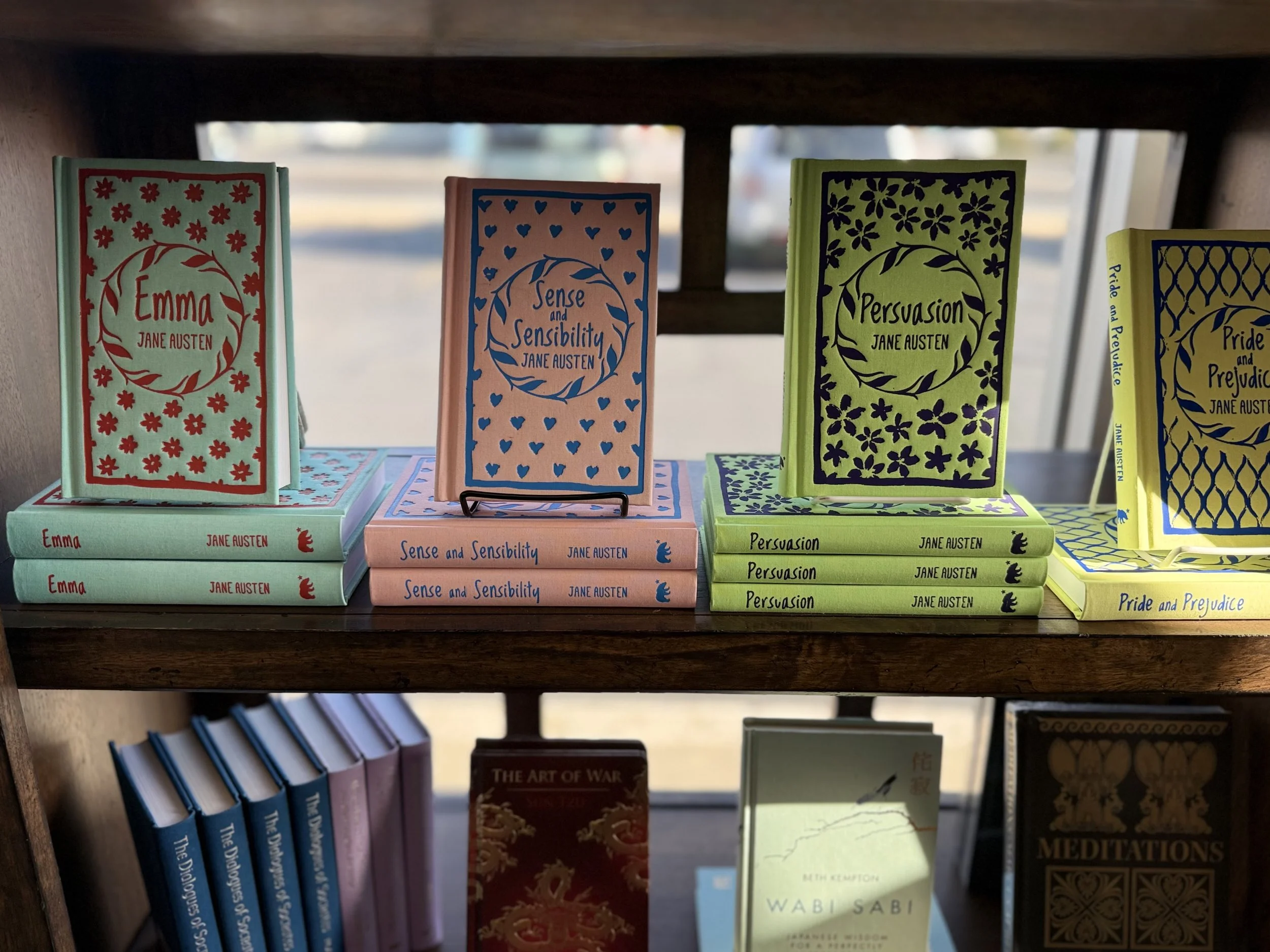

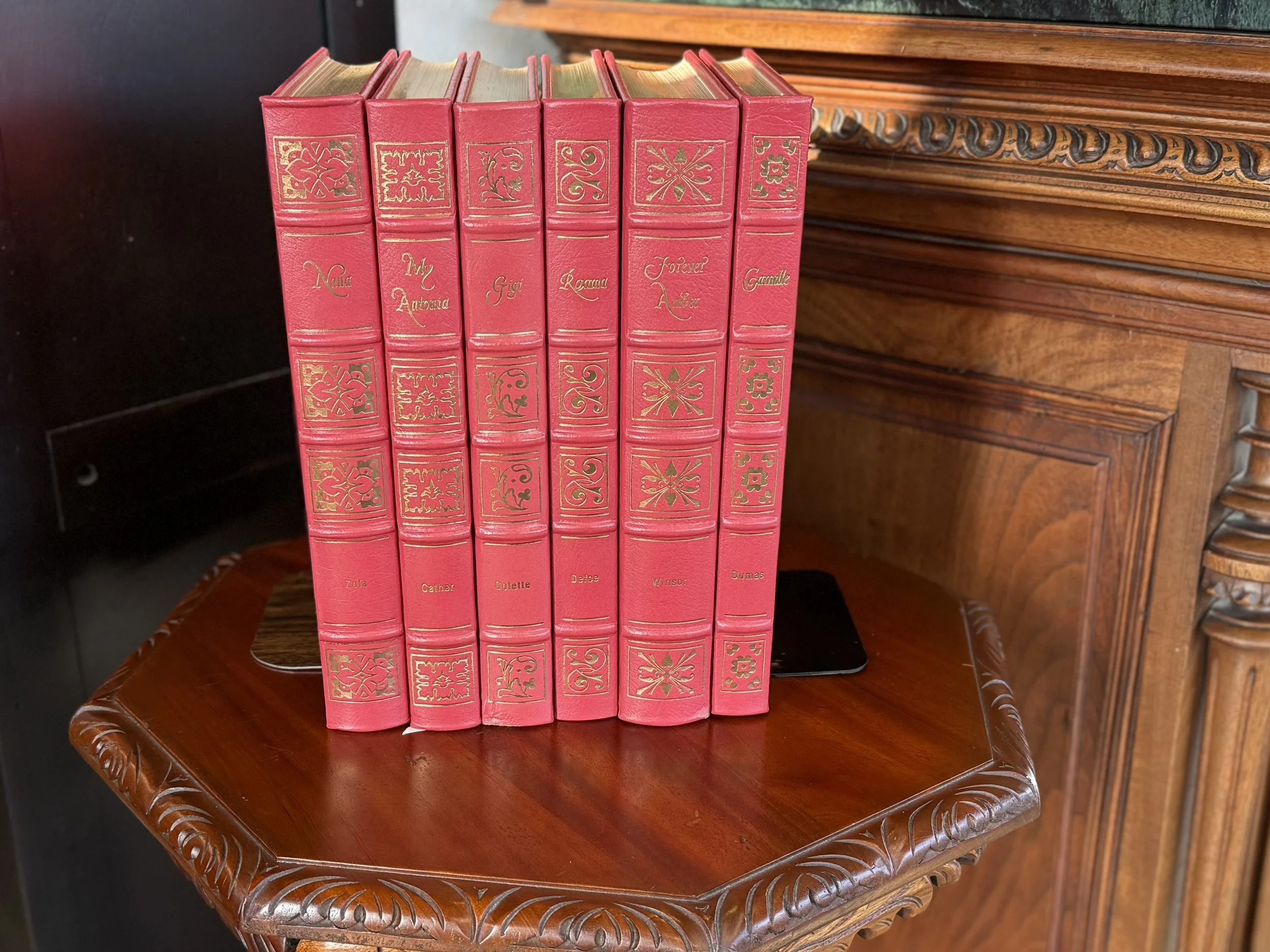

What Cindy has created is also physical, a place that does not rush people. The store feels curated in a way that makes customers slow down - a collision of books and art and antiques, with nooks and crannies that invite you to sit and stay. Cindy loves watching the moment when someone realizes what the building holds. “My favorite thing is to have somebody walk in and gasp.”

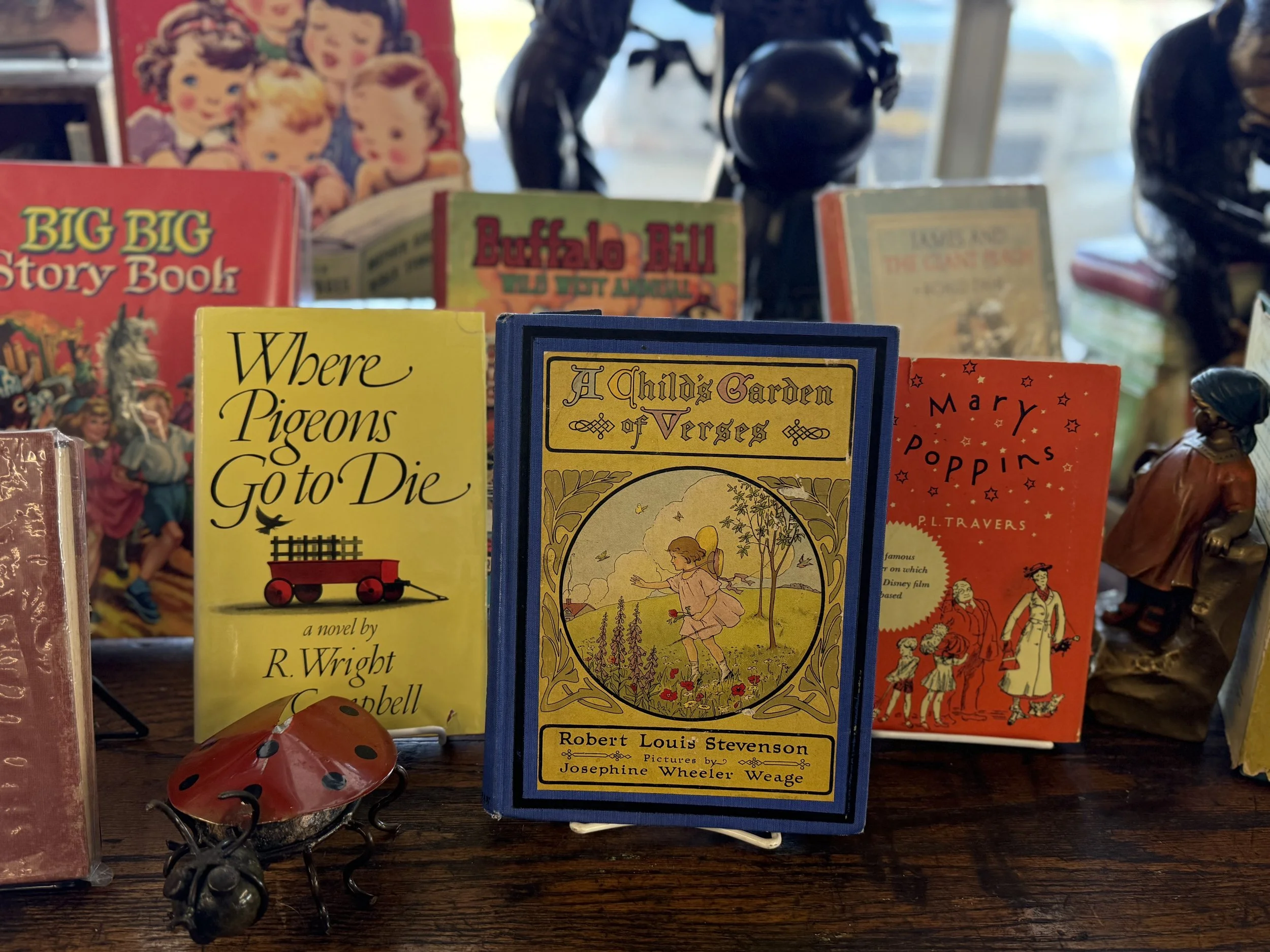

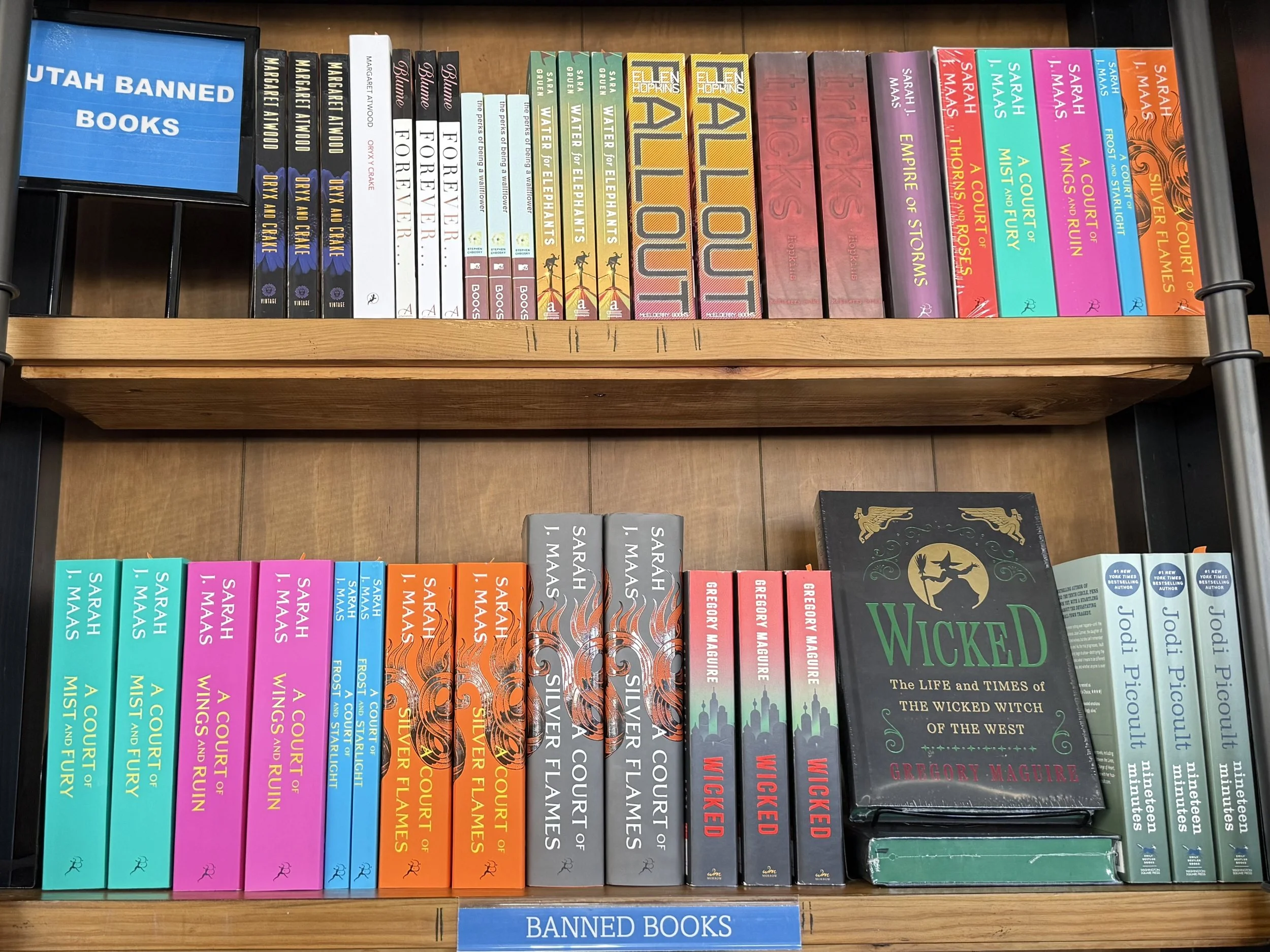

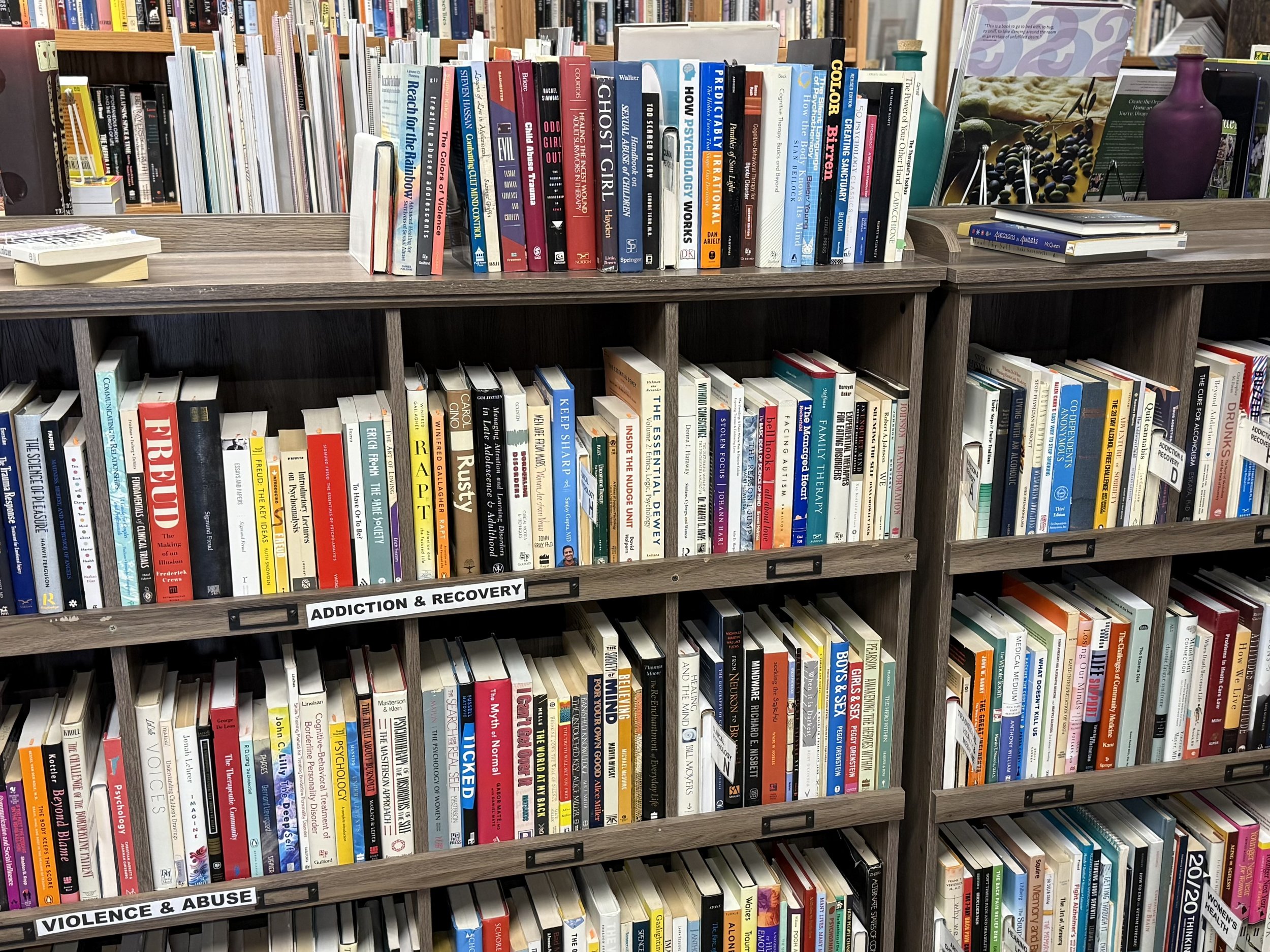

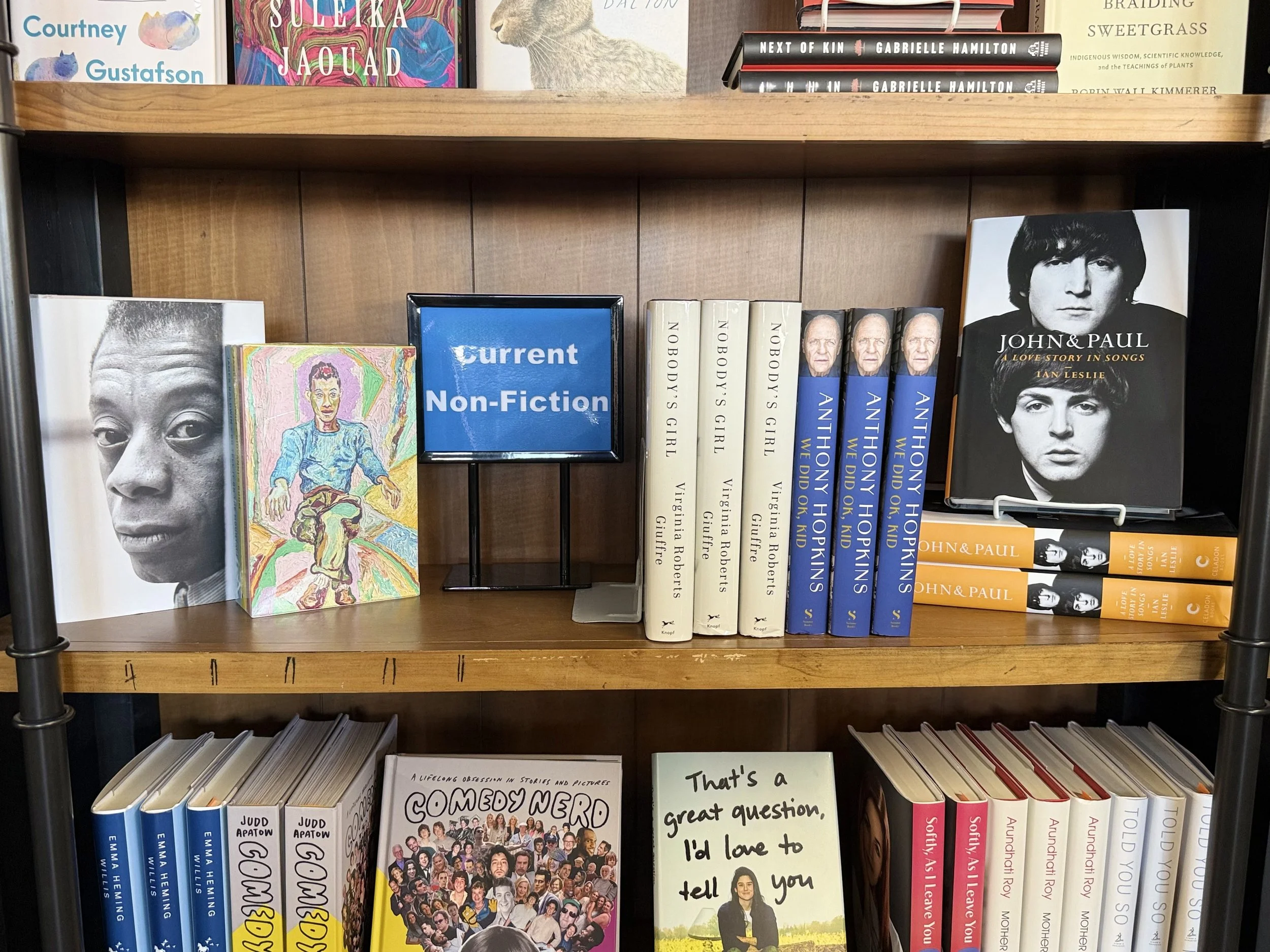

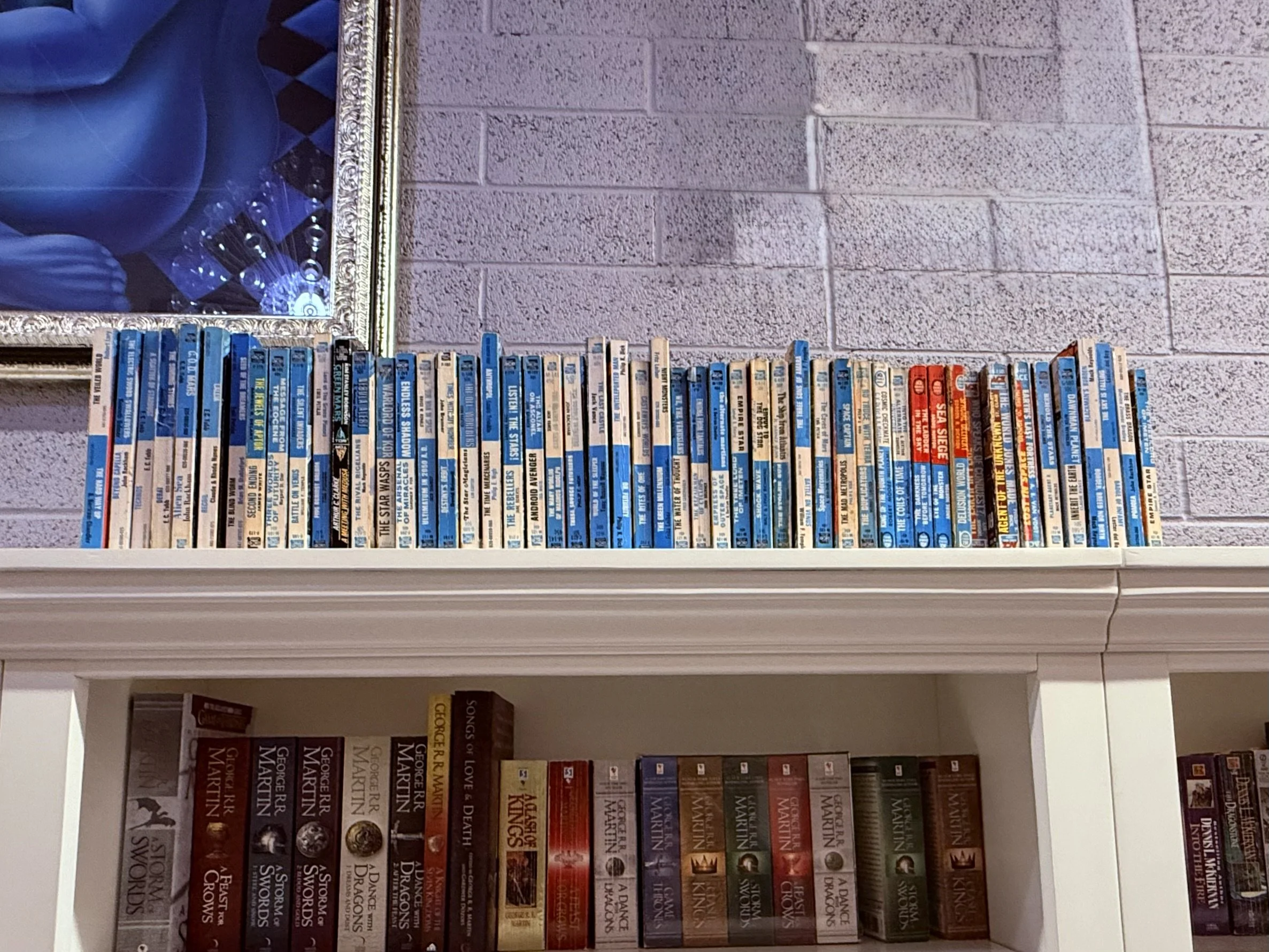

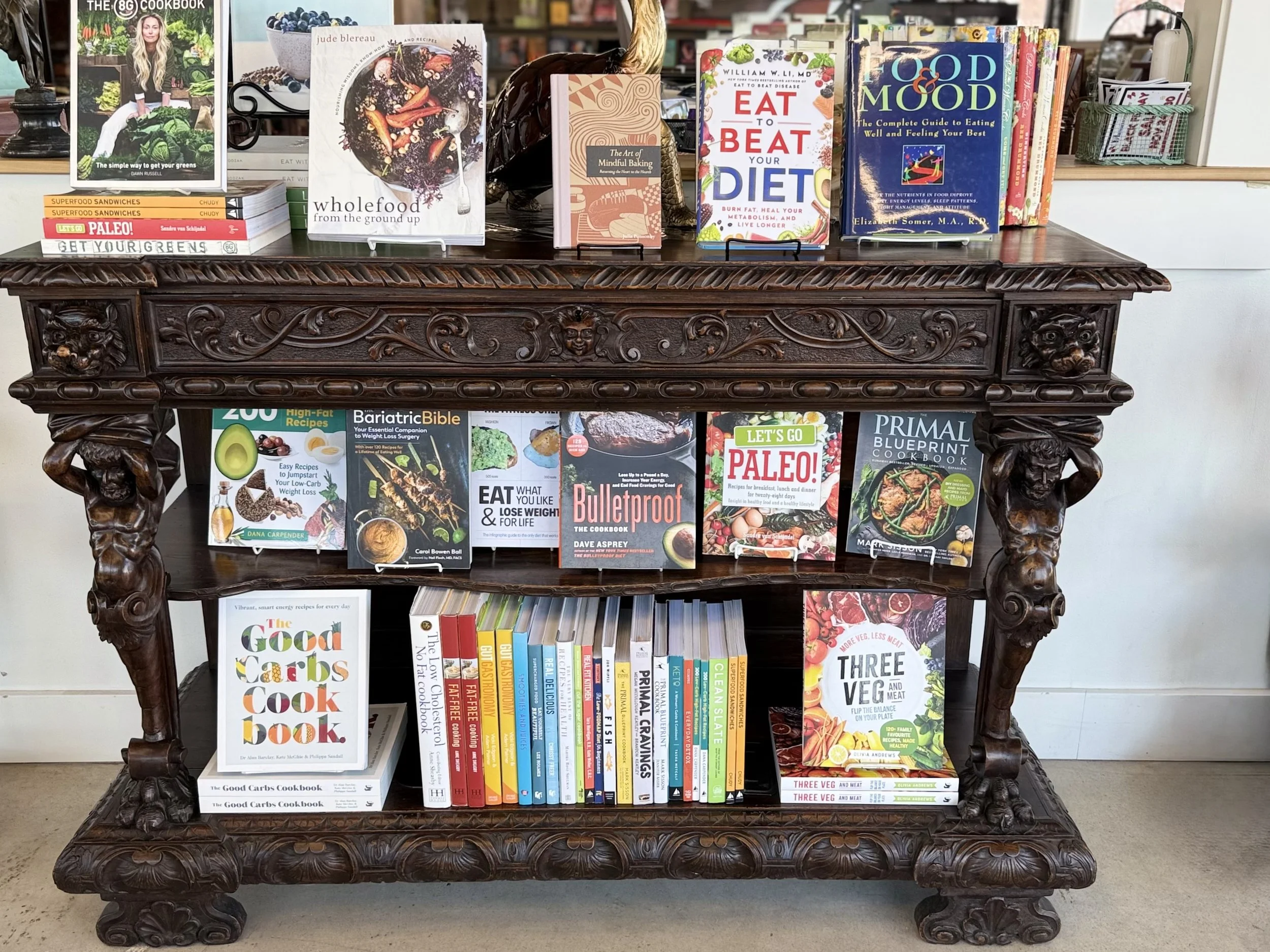

“We do new, used, and vintage.” Cindy is proud of the atmosphere, the sense that each section shifts the mood, as if you are walking from one small bookstore into another, and another, all under one roof. And she is proud that people feel comfortable enough to linger for hours, letting their senses take over - the sight of spines and artwork, the surprise of vintage covers, the comfort of familiarity, the quiet permission to simply be there.

Yet when Cindy talks about what she most wants people to understand about Marissa’s, she does not begin with square footage or inventory systems. She returns to the heart of it, and to the teacher who changed her life. “I do not think a lot of people know the whole story.”

Several times a year, Cindy gives away books - free books for adults, free books for children, and ten free books for teachers who show credentials. She works with schools and tries to solve the hardest part, which is not the generosity, but the logistics - the shipping costs, the limitations of budgets, the hurdles of creating a foundation that can legally solicit funds and expand the reach. “I would like our customers to know that we are really invested in the community.” That investment is not abstract for Cindy. It is personal. “This is because of a teacher who helped me in sixth grade.”

As Cindy’s life grew fuller - her sons grown, her businesses established, her days packed with responsibility - she reached a moment of quiet reckoning. At forty-eight, she realized there was something unfinished, something she had been carrying for decades without fully examining it. She enrolled at the University of Utah.

Cindy decided she wanted a degree in writing, not because she planned to reinvent her career, but because she wanted to understand the process. She wanted to know how stories are shaped, how different points of view alter the truth of a narrative, and how memory, trauma, and time interact on the page. For four years, in the midst of everything else she was managing, she attended classes. The timing finally felt right.

Most of her classmates were young. She would have preferred being surrounded by older students, people with more life experiences behind them, people whose perspectives mirrored her own, but she adapted. She listened. She learned. When instructors offered the familiar directive to “write what you know,” Cindy understood immediately where that road led.

It would have to be about her childhood. Cindy grew up in a home shaped by instability and alcoholism, a place where love existed alongside fear, and where resilience was learned early. Writing about it meant revisiting experiences she had survived rather than examined. It meant putting words to things that had long lived in silence. “My mom had done so much right, but there was so much trauma in our lives at the same time.”

Cindy began writing anyway. Carefully. Slowly. She never felt comfortable pushing the work forward while her mother was alive. She did not want her story to feel like betrayal, even though she understood that telling it honestly was part of understanding herself. The manuscript remained unfinished, evolving quietly as Cindy’s life continued to unfold. In 2026, some sixteen years later, she is still writing that story. She knows that telling it will mean "airing her dirty laundry," but she also believes that "truth has value beyond the self." She hopes that one day, her words might help someone else feel less alone, less confused by the contradictions of loving people who also cause harm.

Cindy also found herself confronting another unanswered question, one she did not yet know how to name. Her father was still alive, and in her mind, he had long been defined as a cruel man. Then, suddenly, everything changed. He suffered a massive brain stem stroke and was diagnosed with locked-in syndrome. For nine months, he existed in a body that could not respond, could not move, could not speak. Cindy chose to become his caretaker alongside her mother. At first, she was emotionally distant, accepting the ending she believed was inevitable. Then one day, she noticed something different. Her father was staring at her in a way that felt like he was seeing her. Cindy paused, unsure, and then asked him to blink if he could understand her. He blinked. “I was resigned to him dying, but all of a sudden I wanted to save his life.”

Cindy knew there was little she could do medically. Comfort was all that remained within her control. But emotionally, something shifted. For the first time, she felt a connection to her father, not the man he had been in her childhood, but the human being in front of her now. She became determined to have whatever relationship was still possible within the confines of that moment. He survived for several more months.

Growing up with her dad had been rough, but the consequences followed long after childhood ended. The stroke was not Cindy’s first confrontation with the damage her father’s alcoholism had caused. When she was thirty-five, she learned of his arrest in a way that still feels surreal. Sitting with her mother, watching the local news, she saw their house appear on the screen. It was there she learned that her father had shot their neighbor.

These experiences did not harden Cindy. They clarified her. They deepened her understanding of compassion, of complexity, of the way people can be both deeply flawed and deeply human. They also sharpened her sense of responsibility, the quiet belief that pain, once understood, can be transformed into something useful.

That belief lives inside Marissa’s. It is there in the way Cindy talks about literacy, about children who struggle, about teachers who need resources, about books as lifelines rather than luxuries. It is there in the free book weekends, in the stacks waiting in the warehouse, in the deliberate effort to place books into hands that might not otherwise hold them. Coming full circle, Cindy cannot help but return to the Nancy Drew book and the teacher who changed her life. “The man who helped me some fifty years ago, I am now passing it forward, and I hope customers know that this shop is invested in all communities. We are trying as hard as we can, and I hope that we are having an impact.”