Dented Brick Distillery

Address: 3100 South Washington Street

Telephone: 801-883-9837

Website: dentedbrick.com

District: South Salt Lake

“Out of deference to the well driller who was shot on this porch, and how important the well is for us, we changed our name to Dented Brick Distillery.” Marc Christiansen revealed this standing a few feet from the barrel room where the air carries warm notes of wood and spice. He had just finished pointing out the original bricks - kept from the old house that once stood on this South Salt Lake property.

Marc’s road began in the southwest corner of Idaho, in the Snake River AVA. “The first winery was St. Chappelle,” he said, remembering the round building with tall windows and Sundays when Gene Harris, the jazz pianist, played to a hillside crowd. He worked in his father’s agricultural supply store, delivering pumps and drip lines - “rudimentary” gear that kept grapes from flooding or molding - then trimmed vines and worked crush at Hell’s Canyon Winery. Wine took root early.

Skiing lured Marc to Utah. After studying economics, a friend pulled him into Park City Ski Resort’s marketing team in 1989. A simple idea - sponsor signposts staked into the snow to guide non-skiers to a World Cup finish tent - turned into an entrepreneurial spark. “I started a company making barricades,” he said. What began as race signage became twenty plus years of building specialty barriers for highways and even airport runways. And then, one sub-zero day on a military tarmac, with a contractor “giving me a hard time about my barricades,” he felt a tug back to what had fascinated him as a kid: fermenters, barrels, and what time does to grain and fruit.

Spirits, not wine, sealed it. Marc had befriended Dave Perkins at High West. “Dave would always tell me how stupid wine was. I should really look at spirits,” he laughed. Marc went to Kentucky with a notebook and open eyes, touring distilleries, sketching flow plans on the office window back home, learning what makes bourbon hum. By 2013, he had investors, a plan, and an order in with Vendome in Louisville. “We opened in April of 2016.

Finding the right site took months. A distillery in the city needed space, specialized construction, and, by federal law, distance from churches and schools. One morning, his realtor called, and told him it was urgent, "come now." Marc pulled up to a modest brick house surrounded by well rigs. The family who owned it had drilled an artesian well here in 1986 - twenty-eight feet of natural head pressure, mineral balance nearly identical to Kentucky spring water, no iron to trouble fermentation. “We knew this was a home run.” They secured the property that day. Cleaning the yard with a crew of investors, someone noticed the front façade: “You know those are bullet holes all over the front of this house?” Marc learned that the well driller had been shot on that porch in 2008. The bricks, the water, the story - they kept the bricks, and they kept the memory in the name.

Inside, the work is both rigorous and lyrical. Steam lines thread into jacketed tanks; a four-roller mill turns grain into fine flour; temperature and pH are tuned for consistency. “We need it to be 145 degrees for conversion to happen,” Marc explained, walking past the mash tun. Alpha-amylase first, then beta-amylase, starch readings until they hit zero, bricks for sugar, glycol loops to pull the heat down to yeast-friendly temperatures. Fermentation runs five to six days; the room doubles as a rickhouse, a warehouse designed for aging spirits - summer heat swelling barrels, winter cold drawing liquid back out, pulling vanilla from oak. “Those oily stains? Honeyholes,” he said with a grin. “Good extraction.”

Then there is the craft you cannot automate. “Lucky for us, the first alcohol that comes off is methyl alcohol,” he said at the spirit safe, explaining heads, hearts, and tails. The art lies in the cut - those last esters that give whiskey its voice without letting harsh notes overwhelm it. For that, Marc relies on his distiller: “Without Harley there would not be a distillery.” Harley came from High West, where he helped create Double Rye. He arrived here at exactly the right time, and he is the quiet compass behind Dented Brick’s profile. Marc, for his part, stepped away from the still after a 2015 surgery severed his olfactory nerve. “I can’t smell anything,” he shared. “I can taste, thank goodness.” He sits at the table with the team and evaluates every batch - blind, with notes - tasting for balance and memory.

The bottles tell the range. Grain-to-glass vodka from half rye and half wheat. A gin that is “super floral and really soft,” made not by traditional vapor distillation but by a week-long maceration of juniper, orange peel, lavender, coriander, fennel, and angelica root, then re-distilled clear. A Chardonnay-finished gin that rests for two years in wine barrels. Rum from turbinado cane sugar out of Louisiana. Whiskeys that spend two years in new oak, then find second lives in cabernet or port barrels. “Port really adds a lot of flavor.”

The tasting room itself is a love letter to problem-solving. When the state and federal rules could not agree on where tastings should happen, Marc measured the line where “tax-paid” space ended. He built a little house with wood trim and cozy nooks so guests could sit, learn, and taste in a place that feels like home. You can settle in for five half ounce pours and a chat. Danielle and Cassie set the tone - welcoming, knowledgeable, never in a hurry.

There is one more story that defines Dented Brick’s soul, and Marc tells it with the quiet excitement of someone who struck a vein. Years ago, while searching antique shops, he found a thick, church-published volume of journals by two brothers from England - Hugh and Henry Moon. The book has since become nearly impossible to find. Inside those pages is a chapter of Utah history that rarely surfaces in polite retellings.

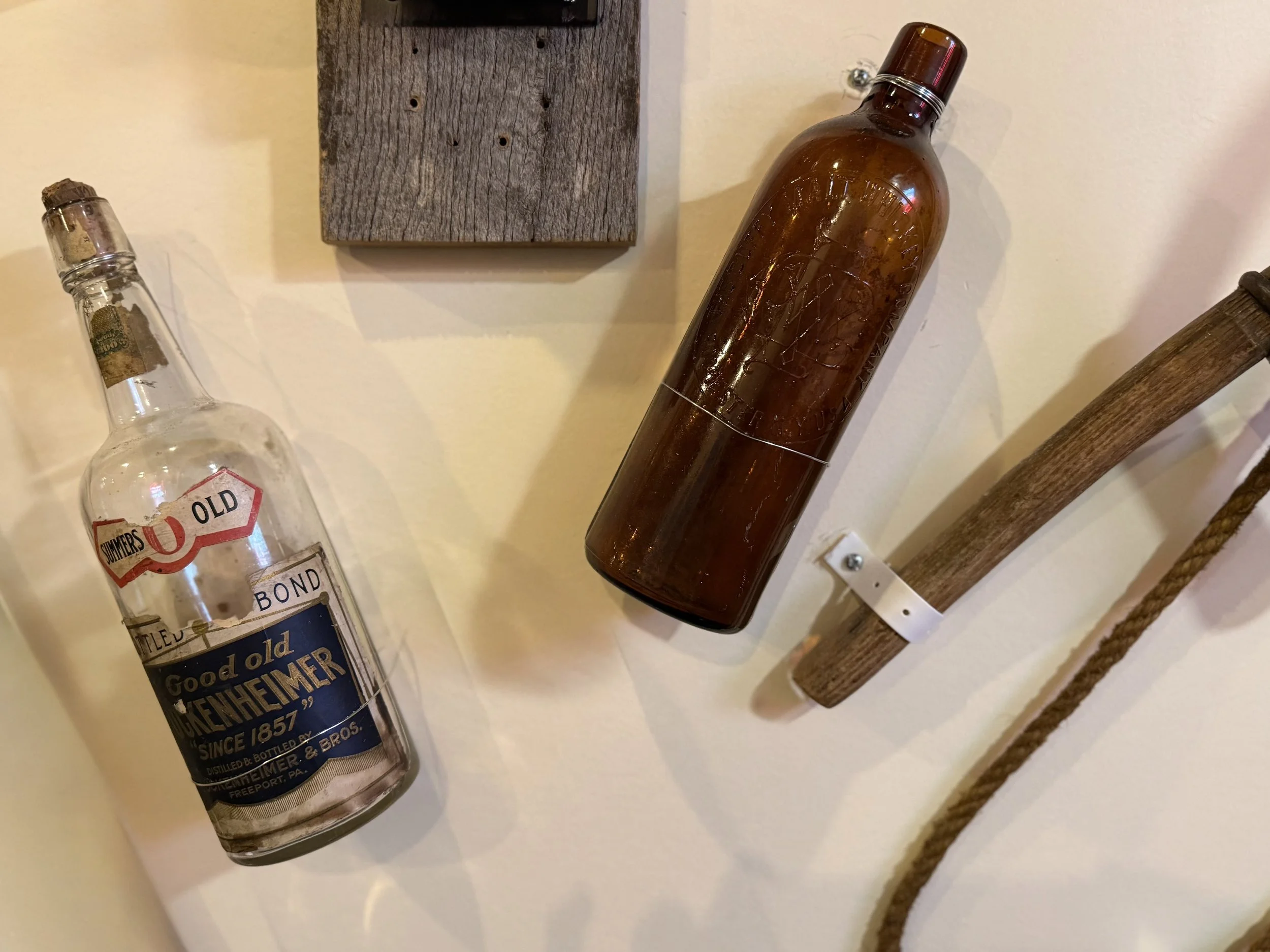

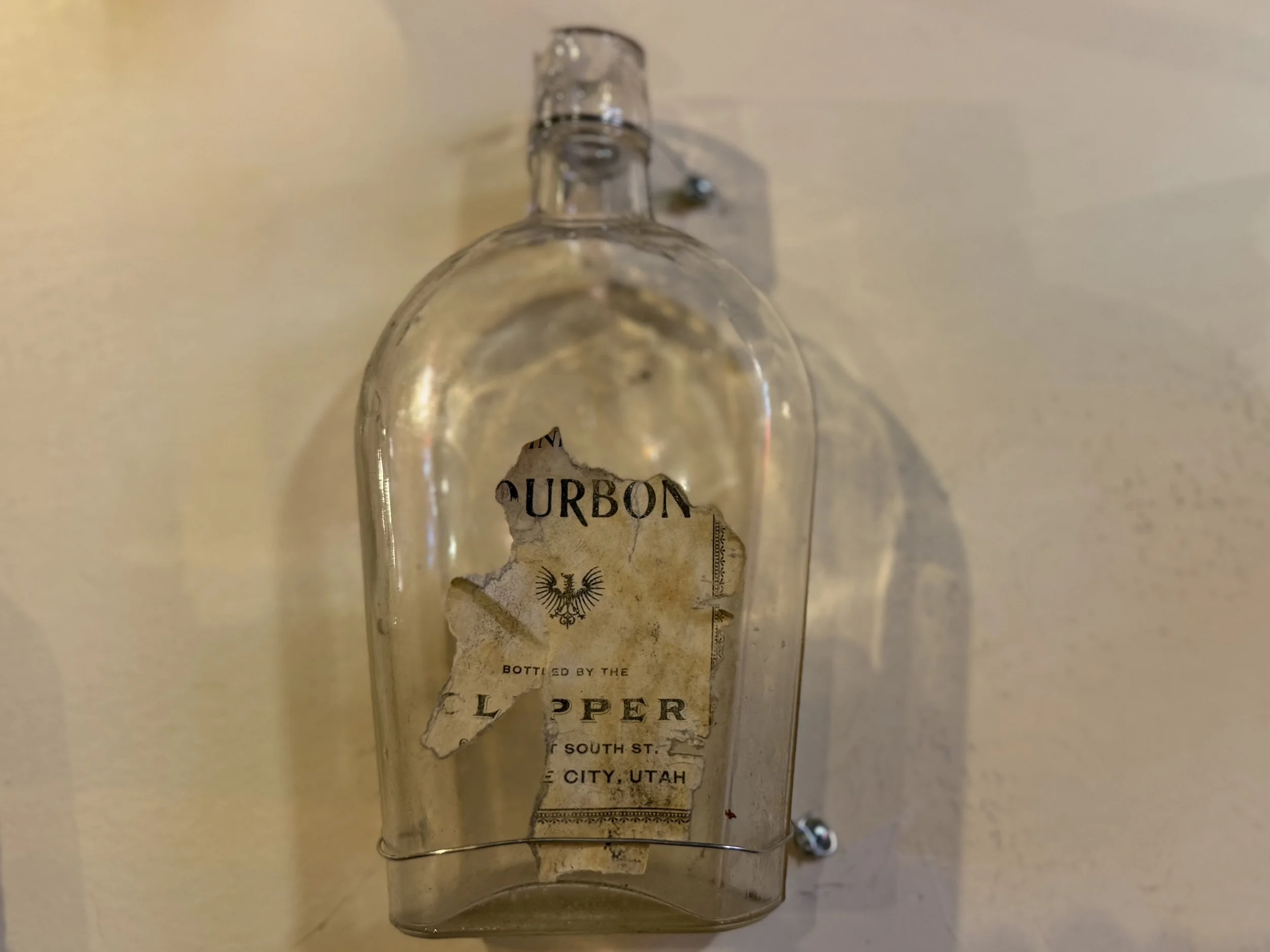

In 1840-41, Heber C. Kimball and Brigham Young sailed to Liverpool to seek converts. An elderly matriarch listened, said no, then later changed her mind and brought in her extended family - some thirty Moons in all. Joseph Smith wanted them not only converted but gathered, so he and his leaders returned to England to bring the family to Nauvoo. The journey took months as winter stranded them in Vermont. They survived and arrived in Illinois in the spring. Among them was Hugh Moon, a literate apprentice distiller who set up a still in Nauvoo and later, after the church’s upheavals and Joseph Smith’s death, came west. In Salt Lake, he distilled again, prospered, and built houses that still stand near Trolley Square. His journals even include Brigham Young’s counsel that the faithful buy whiskey from Mormon distillers. Marc held up an 1880s Salt Lake whiskey bottle - thick glass, rough at the lip - and you could suddenly see the city’s spiritual and spirited histories braiding together. Dented Brick’s super-premium whiskey now bears the Moon family crest and, in some releases, rests in cabernet barrels from Hell’s Canyon Winery, where Marc first learned the rhythms of a cellar - full circle.

Business, like fermentation, has its stressful days. In the fall of 2025, Marc spoke plainly about the Chapter 11 filing. The short version: as the company grew, a 2021 loan changed hands in a murky shuffle; documentation never materialized; a summary judgment went the wrong way; Dented Brick entered a reorganization to protect the distillery while the court sorts out who legally owns that debt. What matters to readers and customers is simple. They are open. They are busy. Sales are strong, with significant back orders, and their original SBA loan is current and uninvolved in the dispute. The case moves slowly, but inside the walls it is business as usual - mashing, distilling, bottling, shipping.

Distribution in Utah works through the state’s control system, where Dented Brick represents itself and appears in stores statewide. Out of state, the three-tier system makes life harder for craft distillers, but Marc is nothing if not resourceful. He is pursuing control-state pathways in places like Oregon and Wyoming, exploring direct-to-consumer platforms that comply with the law, and continuing the quiet work of building relationships with bars and restaurants. Many pour Dented Brick in the well; some commission private labels; others place their gins and ryes right on the menu. The point is never gimmickry. It is flavor, consistency, and a conversation at the bar that ends with a local bottle heading home.

Walk the floor with Marc and he does not rush. He will stop to show you a honey-dark barrel stave, or a bead of condensate on copper, or the way a hydrometer “bounces” when the tails begin. You sense how much of his life is here: youth among orchards, years in the mountains, long nights sketching a distillery he had not yet built, the relief of finding perfect water, the decision to keep the scarred bricks, the luck of finding Harley, the stubbornness to keep going when the business side gets loud. Ask if he still loves it. He shrugs, smiles, and answers the way makers do - by pouring the next glass to taste. Stop by and let someone pour five small tastes. Ask about the cabernet finish and the port finish. Ask about the macerated gin. Ask to see a brick with a dent. And ask about stories of Hugh Moon woven into spirits. “We’re not going anywhere.”