Feldman’s Deli

“I was born in Georgia but came here when I was two. So, this is all I know.” John Feldman’s parents were pulled west by the Olympics and became anchored, unexpectedly, by the mountains. “We came here in 2000. My dad has a PhD in medicinal chemistry. He worked for the Olympics in their drug wing, going from Atlanta for the summer games to Utah for the winter games.”

John's parents had not set out to become restaurant owners. Life nudged them there. John remembers that after his father’s work shifted, stability did not immediately return. “My dad ran a biotech company for quite a few years, and in 2008, it got sold, and he couldn’t find another job after that.” And then, as the years unfolded, the idea that had once felt like a joke in the family became a plan.

John’s mother carried a particular kind of food memory - one shaped by growing up in New Jersey in a Catholic Italian neighborhood. Her parents owned a bakery, and she spent hours there working. “My mom has always been a phenomenal cook. She learned from all the Italian mothers, as well as from her Polish family, particularly when it came to Eastern European Jewish cuisine.” One thing that she was adamant about when discussing the idea with her husband was what kind of restaurant they would open. She spoke up and said, "I never want to open another bakery again. I don’t want those hours.” John laughs at the irony of it now because even though she did not open a bakery, the work she took on demanded the same relentless devotion. Her cooking was never about shortcuts or someone else’s frozen version of comfort. It was instinct and muscle memory and taste.

John’s father brought another thread to the family fabric: Jewish roots, a love of music, a knack for the business side, and the kind of humor that turns identity into a family punchline. “Their joke was, "My dad is Jewish, Janet’s Catholic. The sons are cashews.” John’s voice carries the affectionate amusement of someone who grew up celebrating both Christmas and Hanukkah, and who understands how a family can hold many stories at once.

When his parents began floating the idea of opening a classic New York Jewish-style deli in Utah, the reception was not exactly encouraging. “They kept telling everybody their idea, and their friends said, nope, that will not work in Utah.”

John remembers how consistent the doubt felt. Every doorway came with someone standing in it. Even a potential landlord said no. He told them that he did not think that they could do well and refused to rent them the space that they had wanted. So, they found another spot, one that did not look like the obvious answer at the time. Then John adds the line that only makes sense after you have lived it. "Thankfully, that is probably the best place we could have chosen.”

Feldman’s Deli opened in the fall of 2012, “a week before Thanksgiving.” John was fourteen at the time, old enough to work, young enough to believe it would be easy. “I was excited. I thought it’s a restaurant, the easiest thing in the world. My parents are doing it and I get free food.” At the beginning they kept modest hours - 11:00 - 3:00 Tuesday through Saturday - but the work behind those hours was anything but modest. “My mom was here from six in the morning till about twelve o’clock at night. Every day.”

The deli offered a culinary delight that Salt Lake City had been missing - a real taste of New York deli culture. People came in skeptical and left happily stunned. Early on, something happened that changed the volume of their lives overnight - a review that put their food on the map. John still remembers the instant the momentum turned. “Journalist Ted Scheffler rated our sloppy Joe’s sandwich as number one best in Utah. The next day, we had a line out the door. It was an insane amount of business, and it’s just been up ever since then.”

That is how Feldman’s Deli became what it is now, a place that seats about 55 people and is filled with a loyal following that stretches beyond the neighborhood. “We have people from Boise that drive down just to eat a sandwich and drive back up.” And even after more than a decade, the space still tells the same story - success spilling beyond what the building was built to hold. “With a small kitchen, we’ve done extraordinarily well.”

From the beginning, the division of labor in the family was clear. “Both my parents own it. Michael and Janet Feldman.” John’s father handled the business and marketing end. John’s mother carried the kitchen. And more than that, she carried the education of a workforce that did not grow up with these flavors. “My mom did all the cooking and the training of the employees. Being in Utah, especially in 2012, there were not a lot of people that knew New York, especially Jewish cuisine.”

John grew up inside that world. “This has been my only job. I’ve never had a W2 from anywhere else.” At fourteen, he started where most kids start: dishes, bussing, whatever needed to be done. He next moved into the work that made the deli run, doing all the line cook sandwich making. Then, in a decision that says a lot about him, he chose the job that scared him most because he wanted to become stronger. “I was always a shy, introverted person. I still am, but I knew that was a weakness of mine. When I was sixteen, I began serving the tables in an effort to force myself to speak to people.”

As teenagers, while the deli was becoming a destination, John and his brother Joe were living a different kind of demanding life. They were ski racing at Snowbird. "Racing was our everything.” It meant early mornings, travel, homework on the road, and negotiating school rules just to keep up. We’d go off traveling, always do our homework, and just say, 'Hey, we’re good students, we keep 4.0s, but we need to be allowed more than five tardies a semester.’”

Joe, older by four years, helped launch the deli during the hardest stretch - the opening years - while also trying to move into adulthood. “He was a big part of starting the business. He was trying to manage school, skiing, and opening up the family restaurant. He was a server, and trained all of the other servers, as well as managing that side of the house.” But John also understood something crucial about his brother: “If you ever met Joe, that is not his personality at all.” Joe was built to move. Eventually he chose a path that was right for him - rigging stages for music venues, traveling for work, building a life beyond the deli. John speaks about him with pride and tenderness, as if he wants people to understand that leaving was not abandonment; it was love for the family and respect for what it takes to keep peace. “After two years, he decided to live his own life. He didn’t want to gain any sour taste within the family.”

John did not delay college after high school. He stepped away from racing and enrolled at the University of Utah at the expected time, choosing to major in math because it came naturally to him and felt far removed from the constant pressures of restaurant life. At that point, he did not imagine the deli as his future. Working alongside family had already shown him how quickly business stress could bleed into personal life, and he wanted to explore a different path.

Over time, however, the direction he had chosen began to feel less certain. While he completed the coursework, he struggled to picture himself building a career around abstract numbers and computer screens. The disruption of Covid extended his time in school, and it ultimately took six years to finish his degree. By the time he graduated in 2023, his parents were also approaching a turning point, and it was clear that the future of the deli would soon rest in his hands.

As he stepped into the responsibility of running the restaurant on his own, John recognized another gap. He had grown up in the business and could reproduce his mother’s food instinctively, but he wanted a deeper understanding of cooking itself - technique, structure, and the confidence to create beyond imitation. It was his mother who gently suggested culinary school. He chose a four-month program at the Park City Culinary Institute. I learned two months of baking, two months of cooking.” He chose this path because it fit the reality of his life - no homework, no tests. “I wanted to learn techniques. I didn’t really want to prove my cooking experience to teachers.” And he did it while still showing up at the deli every morning. “I worked from six a.m. to two p.m. at the deli, and then from four p.m. to midnight I was in Park City. For four months I was exhausted, but I’m so glad that I did it.”

It was at this point that Michael and Janet decided that they, too, were exhausted, and it was time for the next generation to become the future whether it is ready or not. “My mom was done. She worked a minimum of sixty hours every week - sometimes up to 100 hours a week. She was so tired.” John stepped in not with a casual handoff, but with the seriousness of someone who understands what he is inheriting. “Once I graduated, I needed to absorb everything my mom had to teach me.”

But “everything” was not a binder of recipes. It was taste, feel, instinct. “I didn’t cook before I owned this place. So, learning how to cook was difficult.” His mother did not measure in teaspoons, and she did not rely on written formulas. “She doesn’t use cups. Teaspoons. It’s all based on how it tastes.” What she taught John, in the end, was not just what to make; it was how to know. “Her method was teaching me not so much the recipes, but how to improve recipes, how to make them taste like hers.”

In time, John felt that he had absorbed a great deal of his mom's knowledge. The deli had trained his palate as surely as it trained his work ethic. He tells a story about potato pancakes - time-consuming, beloved, and easy to ruin in the pursuit of efficiency. “Manuel, the kitchen manager for years, was trying to find a better way to make the potato pancakes. He fried one up, and I had to tell him it doesn’t taste right, it tastes too gummy.” Someone pushed back telling John that he was crazy. "You’re just a kid.” But John stood firm. “Try it and tell me the difference.” When he tasted it, he admitted that I was right." John pauses when he tells this story because he knows it was bigger than pancakes. “That was the first time I felt confident in my tasting abilities. I reminded myself that, oh, I did grow up with the food. I know what it should be like.”

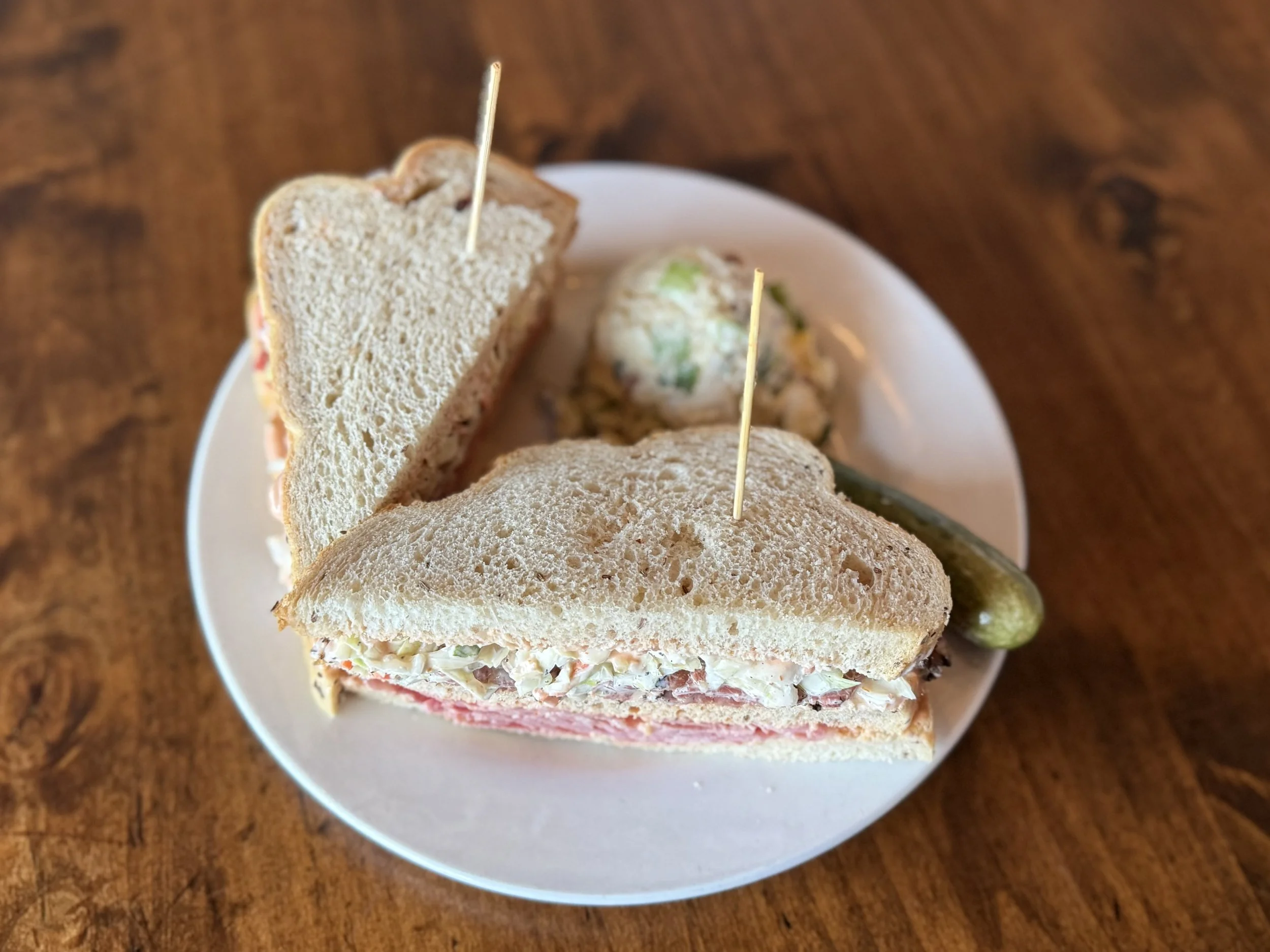

That is the quiet backbone of Feldman’s Deli now. The food is personal. It is not the frozen version of a deli. “If it’s not shipped from New York or Boar’s Head, we make it. They bring in a small list of iconic items and ingredients that are hard to replicate. “We purchase the corned beef, pastrami, cheesecake, black and white cookies, and babka from New York.” Much of the rest is built by hand in the kitchen each day: “Matzah balls, potato pancakes, coleslaw, chicken, tuna and egg salads.”

Even the rye bread became a collaboration because getting it right in Utah takes effort. “We now work with Vosen’s Bread Paradise. "They make us a fully custom recipe.” And the pickles - those half-sours that so many New Yorkers crave - require creativity and relationships. John describes tracking them down through a local European market - European Tastees - that can source what he needs. “Pickles are so hard to get in Utah. I pick them up from Andrew every Tuesday.”

The menu carries the joy and logic of classic deli culture, including the one that keeps selling year after year: The Rachel Sandwich. "It’s grilled with melted Swiss and thousand island dressing. It’s like a Reuben, but instead of the traditional corned beef and sauerkraut it has pastrami and coleslaw.” John smiles at the deli’s internal rule, the kind of line customers remember and repeat: “So if it’s a boy, it’s a Reuben with sauerkraut, and if it’s a Rachel, it is made with coleslaw.”

When his parents ultimately stepped away in 2025, the deli did not stop being a family story. It just changed how the family showed up. “It took my mom about six months to fully stop working here and retire.” But his father still drifts in, a familiar presence who cannot fully let go. “My dad still stops by and messes up my office and then leaves.” He has other loves - golf, skiing, music - and yet the deli remains part of him. “He’s his own musical artist, and he plays all around the city. He hires the local bands that play Friday and Saturday nights here.”

John now runs “everything,” which is both a point of pride and an honest challenge. He speaks plainly about how much his mother did, and how impossible it is to replicate her output without replicating her exhaustion. “So, now I’m doing my mom’s job and my dad’s job. It has been difficult to do it all. My mom used to have specials, used to have soups every single week, but she also worked hours on end to do all those things.” John is trying to do it at a slower, more methodical pace. There is no doubt that he is doing a phenomenal job and when he is ready, he can add whatever else he feels he and his staff can handle.

John shares his story with the same tone he uses when he talks about customers. He is grateful, steady, and clear-eyed about what service work costs a person. He has a message he hopes people will hear, not just about Feldman’s Deli, but about any place where someone is working hard behind a counter. “My biggest thing is people don’t see service workers as human beings. Especially on a computer when they’re writing reviews." He wants people to remember that they are writing a review about someone’s business, their livelihood.” John is not asking people to lower their standards. He is asking them to remember the people in the room. “We’re humans, we work really long hours. Mistakes happen. Just be patient. If something’s not right, and you email me or talk to me when you’re at the deli, we are happy to replace it. We don’t want anyone to leave having had a dissatisfied experience.”

That is the heart of Feldman’s Deli - a mom-and-pop leap that turned into a legacy, and a twenty-seven-year-old son who grew up inside the work, learned the taste of home by repetition, and now carries the responsibility with a kind of grounded reverence. John continues to adhere to his mother’s standards in every bite, still showing up before dawn, and still believing that the food is only half the story. “What my parents built was something the world told them would not work. And they made it into a place people drive hours for, just to eat a sandwich.”