Soleil Nail Studio

Address: 254 East 100 South

Telephone: 385-481-7832

Website: soleilnailstudio.com

District: Central City

“I have felt it in my bones since I was very, very young. I was going to accomplish big things.” Vayanna Kruse, owner of Soleil Nail Studio, grew up in a small Iowa town. But even as a child, she sensed her life would lead her somewhere else.

Ambitious from the start, Vayanna threw herself into competitive sports, dance, and soccer from the age of two. She also dabbled in entrepreneurial ventures - baking for her grandmother’s art shows, tie-dye projects, and other kid-sized businesses. She worked on farms with every type of livestock, always eager to learn something new. Still, the pull toward a bigger life was constant.

At nineteen, a relationship made Vayanna realize that the growth she craved would not happen if she stayed in Iowa. Within two weeks, she decided to move to Utah, fitting what she could into her car, bringing along her six-month-old dog, and heading west in 2017. She stayed with her aunt for the first two years, working as a professional nanny - a role she had held since she was seventeen - for several high-end families. At the same time, she explored other interests, taking acting classes and modeling, until her career path began to shift.

In 2020, Vayanna took a position with a luxury home development agency in Park City, managing a team and caring for property owners. From there, she became an executive assistant for the CEO of Utah’s professional rugby team, quickly moving into the role of executive operations manager. By 2024, however, she was feeling the weight of corporate life. “I quit on a whim - no plan, no idea what I was doing next. I just knew I had to get out before it quite literally killed me.”

Vayanna remembered an apprenticeship program for nail education she had seen the year before. It seemed unlikely, yet the idea stuck. As a creative and a painter who had been doing nails for fun since she was twelve, she began to see the potential in making it her career. She started her apprenticeship in August, working under her future business partner and co-owner, Chasey Knight, and received her license in December 2024.

Just a month later, Vayanna and Chasey were working in what they describe as a “toxic environment” and decided to build something of their own. Within a month, they had found a downtown Salt Lake City space, secured private investment, and launched Soleil Nail Studio on March 2, 2025. From the start, the business took off, exceeding Vayanna’s expectations each day.

The partners designed Soleil to be unlike any other salon in Utah. Prioritizing natural nail health, they operate as an odor-free space with no acrylics or regular polish, customizing every service to the client’s lifestyle and nail condition. They offer multiple brands and product types, so each guest receives the best fit for their needs. Every service ends with hot towels and lotion.

"Soleil is also the only standalone luxury nail salon in the state with zero-gravity steam pedicure chairs" - a more hygienic, waterless system that uses steam to open pores before a mud mask, body polish, and massage. “When people come in and experience it, they don’t go anywhere else after,” she said with a smile.

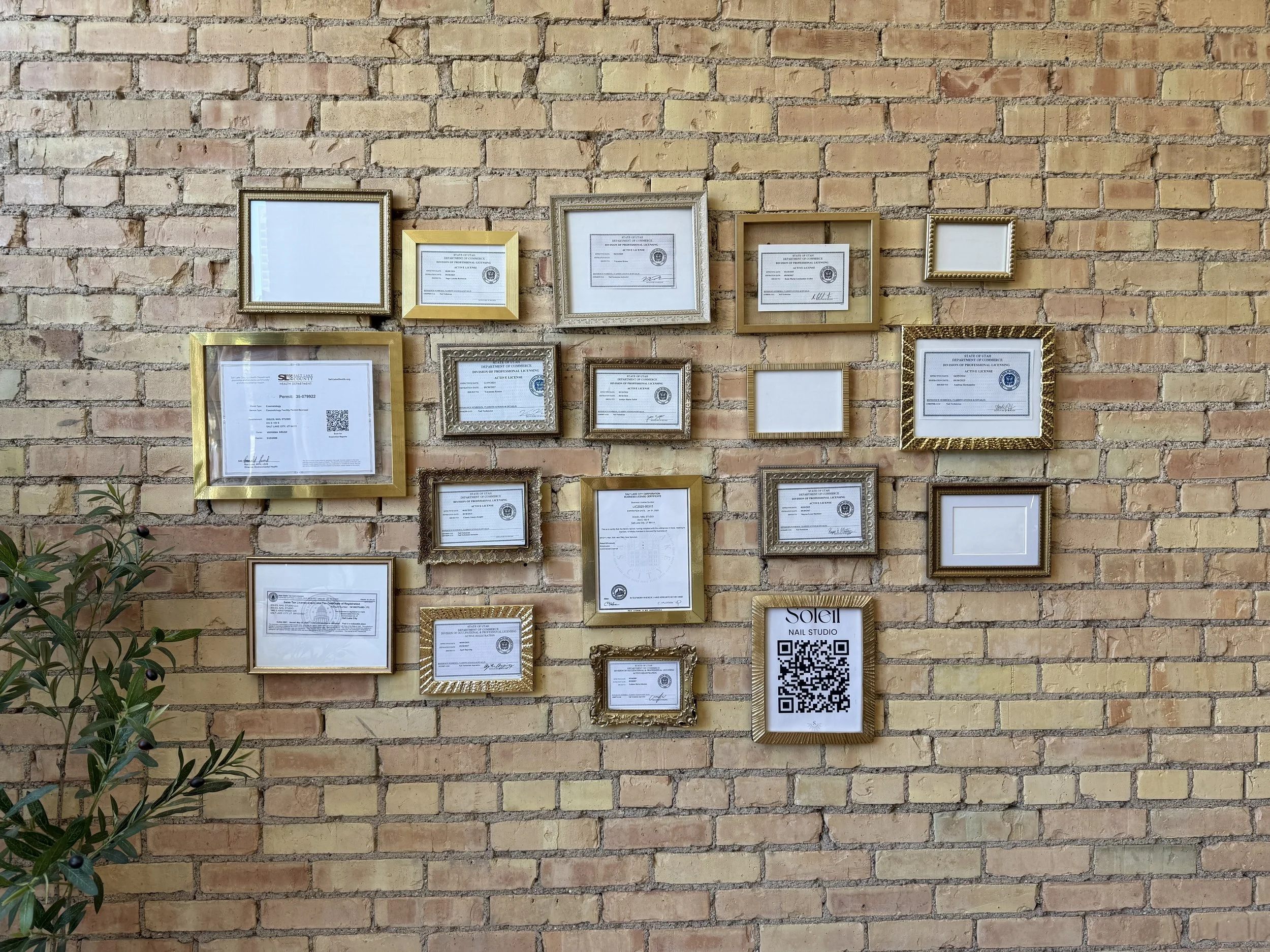

When Vayanna and Chasey took over the space, it was an open, neon-green-walled marketing office. They transformed it into a warm, home-like environment with neutral tones, leather, brick, and rounded edges for a psychologically comforting feel. They wanted a place where “anyone can belong - from a teenager with an alternative style to an older woman who loves a cozy space.”

Affordability and fairness are equally important. Soleil offers an apprenticeship program where students can train while earning commissions and keeping 100% of their tips. Licensed nail techs start at a forty-five percent commission - a rate many in the industry wait years to achieve - because Vayanna believes in paying them what they deserve. She insists on a healthy work-life balance, organizes team events, and holds quarterly check-ins to ensure the staff is thriving.

Though Chasey has since stepped down from ownership, she remains part of the team as a nail technician and teacher. Vayanna is now the sole owner, confident in her ability to lead and expand. Her five-year plan includes opening multiple locations in Utah before branching into the Midwest and South, where she sees a need for the services Soleil provides.

Vayanna’s vision for change goes beyond the salon. She dreams of creating an insurance company specifically for the beauty industry to provide benefits and maternity leave - resources that are nearly nonexistent in her field. “I’m supportive of all these things,” she said. “I need Soleil to grow so I can make them happen.”

Every detail at Soleil reflects her belief that success comes from passion, intention, and care for clients, for staff, and for the industry as a whole. “If anyone can do it, it’s you,” her team tells her. And she believes them. “I have faith in myself. I know I can scale this business to the empire I want to create.”