Salt Lake Acting Company

Address: 168 West 500 North

Telephone: 801-363-7522

Website: saltlakeactingcompany.org

District: Marmalade

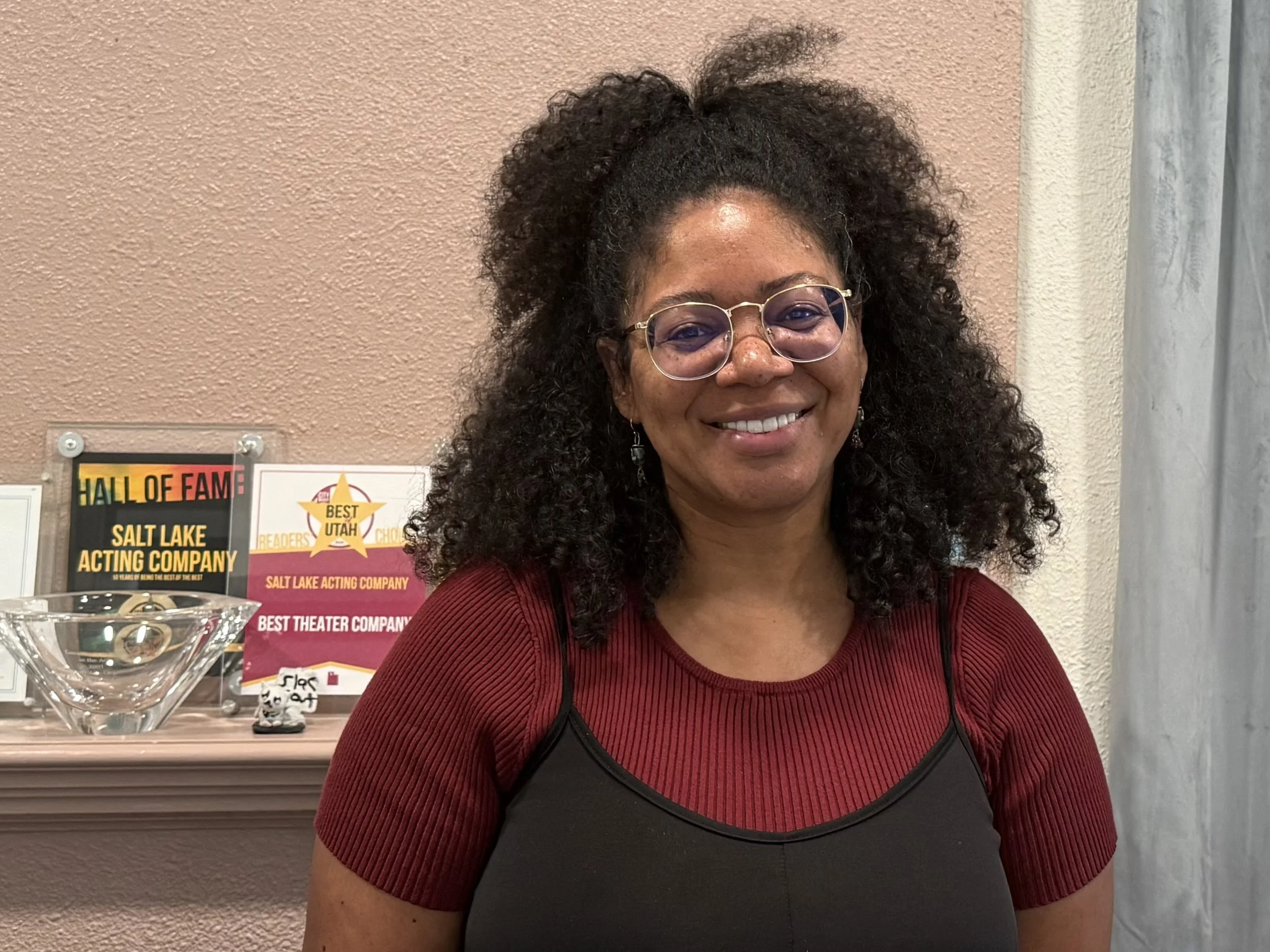

“It was never in the cards for me. Never in my wildest dreams would I have imagined that I would be running a theater company - let alone Salt Lake Acting Company. Cynthia Fleming grew up in Bountiful, Utah, the daughter of a former Miss Utah and a charismatic father who managed a radio station and often emceed events around Salt Lake City. Tall, lanky, and pigeon-toed, she was steered toward ballet at the age of seven. Her teacher, a Utah Civic Ballet (now Ballet West) dancer, gave her strict classical training, and she quickly went from being one of the weakest in class to one of the best.

By the time Cynthia was twelve, she was immersed in the University of Utah’s summer dance program, where she discovered jazz - a style that embraced her height and angularity in ways ballet never had. She majored in ballet with a musical theater emphasis at the University of Utah. This program, created by Rowland Butler, allowed students to study across the colleges of music, dance, and theater. It was a brilliant structure that gave Cynthia the best of both worlds. Ballet had instilled discipline, but it also came with relentless pressure to lose weight, which left her injured with shin splints. “They wanted us to lose so much weight, and I realized, wait, I can still dance, but I don’t have to sacrifice my health,” she recalled.

Shy and reserved by nature, Cynthia had to teach herself to get out there and stand on a stage. She had never sung before, but she knew that if she wanted to perform in musicals, she would have to find her voice. Slowly, she pushed herself to sing, even if it terrified her. “I could hardly say my name out loud to a stranger,” she admitted. “But I taught myself to be brave. I knew if I wanted to do musicals, I had to get over that fear.”

Shifting from ballet to theater gave Cynthia the freedom she was craving. She could still dance at a high level while expanding into acting and singing, and she discovered that theater offered a wider canvas for her talent and personality. She performed at the Opera House, in summer repertory at Lagoon, and even in Kismet at Pioneer Theatre. That foundation, she said, meant that when she eventually left Utah for Los Angeles and New York, she was already working at a professional level.

In 1979, after a year in Los Angeles, Cynthia tried out for A Chorus Line. Out of 150 women, she was called back and eventually cast as Judy Turner, one of the auditioners in the musical. She also understudied the characters of Cassie and Sheila. She toured the country beginning in November 1979 and later joined the Broadway company.

When the tour stopped in Salt Lake City, Cynthia vowed she would not come home as just an understudy. Fortune intervened. First, she went on as Judy. Then, when Sheila fell ill, she raced to change costumes, begged her dresser to call her mother, and the company held the curtain until her parents - out gardening - arrived at the theater. That night she performed Sheila. And on closing day, during the opening number, Cassie fell and injured her ankle. By the time the number was over, Cynthia had stepped into the lead role. “My parents got to see me in all three parts in one week,” she said. “It was the perfect way to thank them for all their support and love.”

Cynthia stayed with A Chorus Line until the show closed on Broadway in 1990. By then, she had been married to her husband Jeff for nearly a decade, and they were raising their first son, Anthony, who had been born in Chicago in 1983. When the curtain finally fell on A Chorus Line, Cynthia knew it was the right moment to step away from performing, focus on her family, and pursue a new path. In 1993, she and Jeff welcomed their second son, Nicholas. Around the same time, she began working at Bloomingdale’s as a Lancôme makeup artist. She credits the job with giving her an unexpected education in human connection. “Those twenty minutes at the counter felt like real theater,” she said. “I learned how to communicate with strangers, and it has helped me ever since.”

By 1994, life in New York had begun to feel limiting. Cynthia and Jeff realized that much of what they were doing professionally could just as easily be done in Salt Lake City. There, they would also be closer to her family and could raise their children in a more grounded environment. In August of that year, they moved back to Utah.

Soon after, a friend who was directing a play at the Egyptian Theatre asked Cynthia if she could choreograph a number. She had never choreographed before, but she said yes. With a ten-month-old at home, the chance to get out of the house and return to theater was irresistible. She leaned on friends for advice, figured it out, and the production was a success. That led to her being asked to choreograph Gunmetal Blues at Salt Lake Acting Company - a turning point that reconnected her with the theater where she had first performed in 1978.

Throughout the mid-1990s, Cynthia assisted with directing, choreographed Saturday’s Voyeur, and even helped with subscriber phone calls. In 1998, she was hired full time to help grow and retain subscriptions. SLAC had fewer than 900 subscribers then, but by the time she and her team hit their stride, the numbers had tripled.

A decade later, Cynthia nearly walked away. By 2009, she was ready to quit. The hours were long, the challenges endless, and she told her husband she was done. But Jeff, normally supportive of her every career move, stopped her. “It was the first time he ever said no to me about work,” she remembered. He reminded her that the family depended on her income, however modest, and urged her to find a way to make it meaningful again.

So, instead of resigning, Cynthia reinvented her role. She created a communications team, placing herself as director, and began restructuring the organization from the inside. It was a gamble, but it worked. Energy surged through the theater, new systems were put in place, and SLAC began to thrive. After serving as co-producer with Kevin Myhre, she was named Executive Artistic Director in 2015. Today, she leads with equal parts artistic vision and business acumen, a balance she attributes to handling finances throughout her marriage and her innate love of numbers.

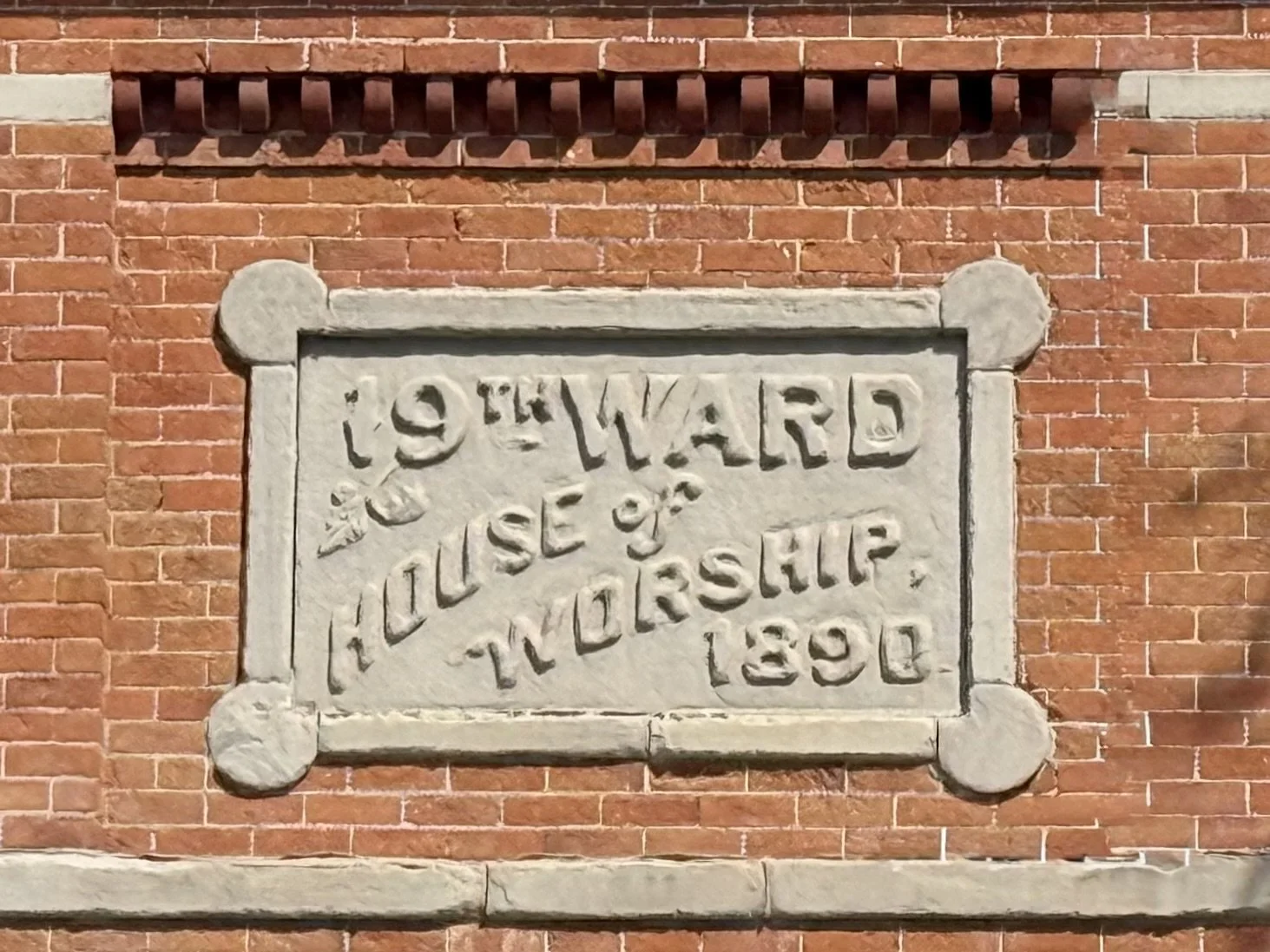

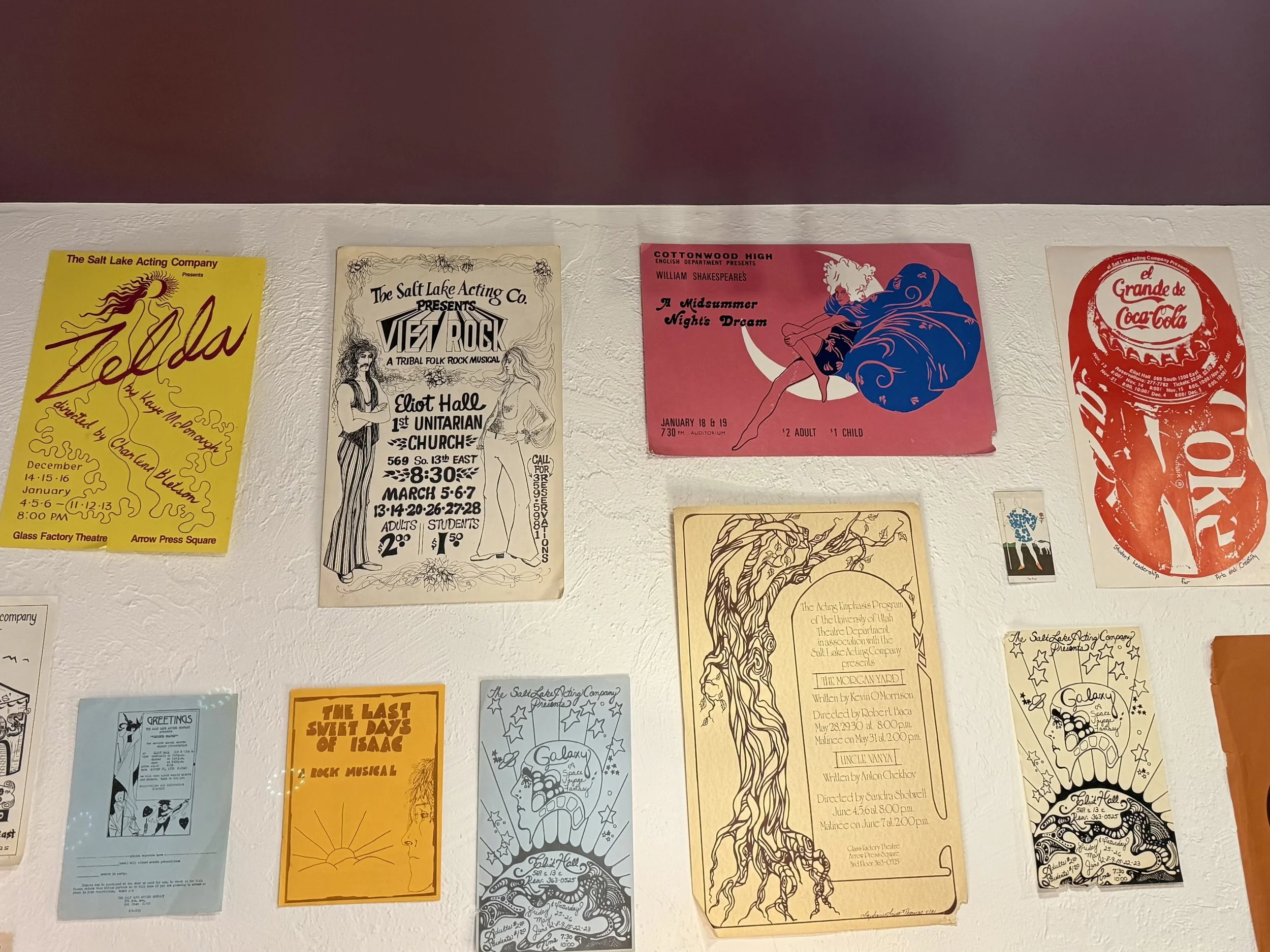

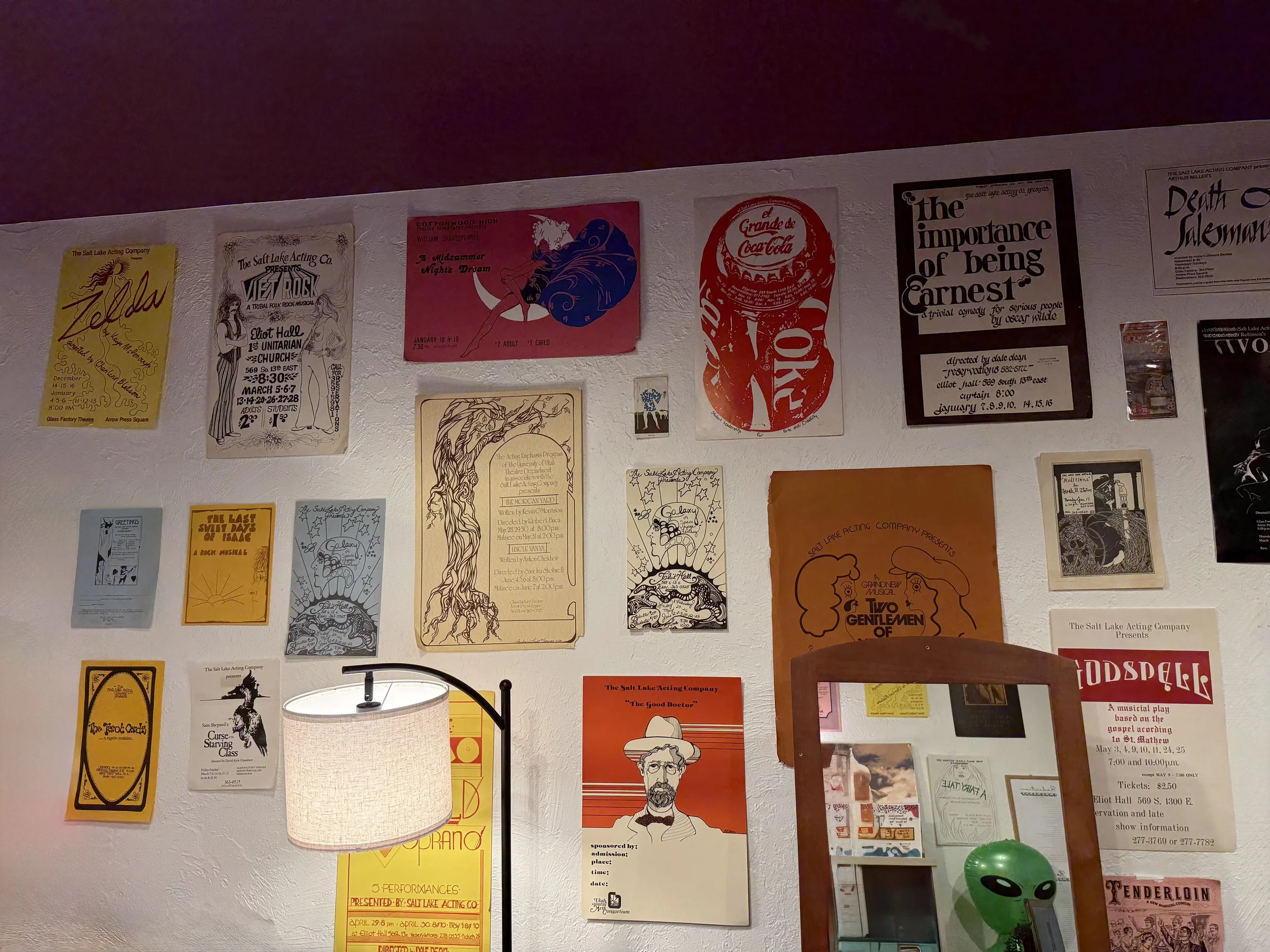

Salt Lake Acting Company itself has a rich and unconventional history. Founded in 1970 in the basement of the Unitarian Church, the company quickly made its mark producing daring plays that would otherwise never have been seen in conservative Utah - Viet Rock, a rock musical first staged in 1966 that inspired Hair, and Turds from Hell, a 1972 play involving absurd travel through a world of angels and devils, among others. In the late 1970s, SLAC moved into its current home, a former LDS church built in 1895. The building’s Russian architecture and upstairs gymnasium space became part of its identity.

Over the decades, SLAC continues to be known for producing contemporary work, often introducing Utah audiences to plays before larger theaters dared to stage them. Cynthia recalled securing the rights to Fun Home, a groundbreaking musical that toured nationally but skipped Salt Lake City. “They told us, this play is important, and it should be seen. And we were the only theater brave enough to do it,” she said. Productions like Fun Home, Bat Boy, and Passing Strange have kept the company at the forefront of bold, inclusive storytelling.

Cynthia has also overseen major improvements to the historic building, investing more than $1.5 million during her tenure to make it fully accessible. Before COVID, SLAC had grown its subscriber base to nearly 4,000; after the pandemic, it dropped back to around 800. In 2025, Cynthia and her team are rebuilding, with subscriptions recently reaching 2,300. Her goal is to return to at least the 4,000 level.

What makes Salt Lake Acting Company unique, Cynthia believes, is not just the building or the plays, but the people. The staff - all artists themselves - host every show, welcoming each audience member personally. The community, too, has sustained the theater, with grassroots fundraising and thousands of small donations ensuring its survival even when federal or corporate funding was unavailable.

Cynthia is committed to the theater’s mission of presenting brave, authentic work. “I think this theater is one of the most special in the country,” she said. “Its soul has remained intact through every leader, always bringing stories to Utah that wouldn’t be told otherwise. And as long as I can stay relevant, I’ll keep fighting for that.”